This post, first added in 2011, has now been edited to add all of the information I have written on the topic since. The latest was added in January 2020. Illustrations also appear in the posts which follow, which duplicate some of the text.

When the American Revolution began in 1775, Schaghticoke was a sparsely populated region. It had been on Albany’s frontier with Canada for many years. The citizens remembered Indian raids in the past, and some of the men had been in the colonial militia during the French and Indian Wars. Some had gone as far as Canada as part of English offensives against the French. There was a small fort in the Albany Corporation Lands, near where the Knickerbocker Mansion is now, but it was made of logs and was in poor condition. The last time it had been garrisoned was probably around 1750. So while the residents had lived a peaceful life since the end of the French Wars in 1763, they remembered the danger there had been before, and knew that the fort they had would not protect them.

The Revolution was our first Civil War- just think how you would feel now if over the course of a few months you were expected to abandon your long-time support of your King and country and transfer allegiance to a rudimentary and untested new country with no money and tenuous leadership, plus fight in a war to become independent. This was a difficult and fraught time for everyone.

When the Revolution began, the former colony of New York set up a provincial Congress on a statewide basis, and Committees of Correspondence for the counties. It is not clear from reading the minutes of the Albany committee how the representatives were chosen. The men met about every two weeks, generally in Albany, developing a new government and organizing to fight a war. The minutes of the committee begin in January 1775 with an oath of secrecy and loyalty. John Knickerbocker and John Wandelaer, both residents of the Albany Corporation lands, were the first representatives of Schaghticoke. From the minutes I have read, they concentrated on supporting the war with men and materiel and discovering those disloyal to the Revolution. Michael Overocker, Samuel Ketchum, and Michael Vandercook of the Pittstown region soon began representing the Schaghticoke district. John Knickerbocker became the first Colonel of the local militia regiment, the 14th Albany.

A sub-committee of the Committee of Correspondence was the Commission for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. Their task was to root out Loyalist or Tory activity in the county. Over the course of the war, a number of men were accused of supporting the enemy or being lukewarm in their support of the Revolution. In one meeting in 1779, Peter Yates, who had taken over as Colonel of the 14th Albany County Militia, told the Committee of Correspondence that several strangers had moved into town who had collected cattle for the British army at the time of the battle of Saratoga in 1777, and that “those persons daily obstruct the execution of the orders of the militia officers.” The men included a couple who became prominent members of the post-war community, so apparently the accusations came to nothing. Yates also charged that a young man who was due to become a Lieutenant in the regiment, Jacob Hallenbeck, was “an enemy to the American Cause.” As he is on the list of Lieutenants, this must also have been disproved.

In July 1779, Joseph Jadwin, a “yeoman of Schatikoke”, put up bail for a fellow citizen, William Flood, who had been in jail, as he “might prove dangerous to the Safety of the State,” stating that he would keep him on his farm and guarantee his good behavior. Jadwin is on the list of soldiers in the 14th Albany County Militia.

In one interchange at a meeting of the Committee of Correspondence in 1781, Lt. Jonathan Brown, who was from Pittstown, was directed to arrest Simeon Smith of “Pits Town”, innkeeper, on the charge that he “entertains disaffected persons, drink’s King George’s health and speaks disrespectfully of the authority of this state.” Smith appeared before the Committee with Brown, and was released after posting 100 pounds bail and being examined by the Committee on Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. I must note that Simeon appears on the list of men who served in the local militia unit during the war. He was brought in on the testimony of another resident, Samuel Stringer, who was another member of the Committee of Correspondence.

There was concern throughout all of the colonies that some if not many people did not support the rebellion against Great Britain. Of course this would be a difficult choice for anyone: known versus unknown, settled government vs. everything new. There was special concern about Loyalists in a frontier area like Schaghticoke, where there could be easy infiltration of the British and their allies. It was necessary to prevent the British from getting support from local residents. In some areas, for example in what is now Washington County, there were many Tories. The military commander of the whole northern region until the battle of Saratoga, General Phillip Schuyler, was himself repeatedly accused of secret loyalty to Britain.

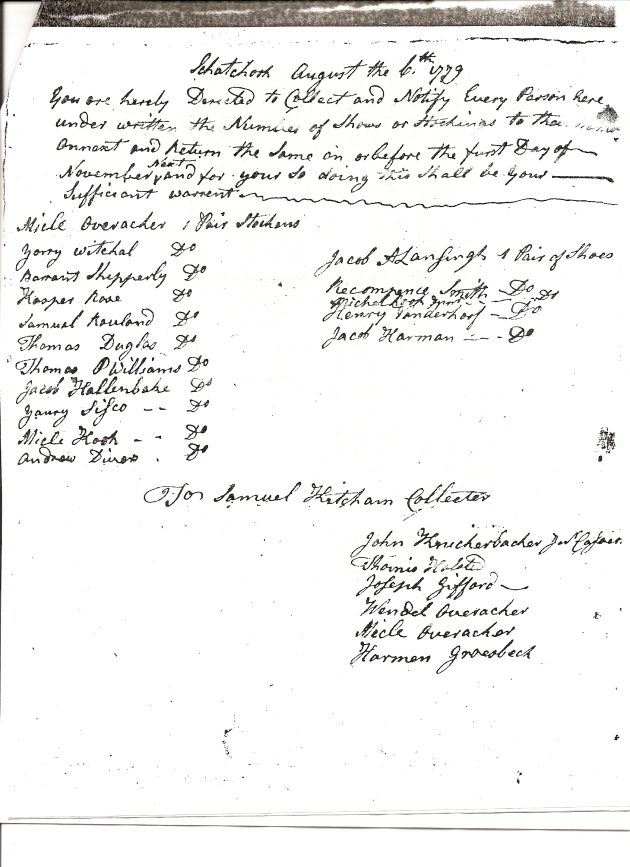

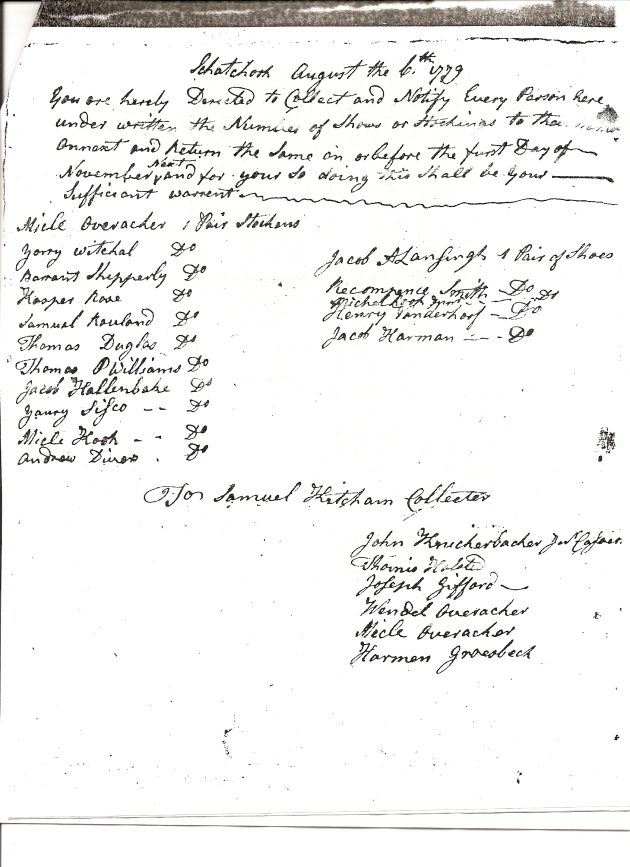

The men from the Schaghticoke district who served on the Committee of Correspondence acted as a local government, at least for prosecution of the war. The town of Schaghticoke owns a wonderful document titled “Schatckook, August the 6th, 1779” listing persons who were to provide either a pair of stockings or shoes for the troops by the 1st of November. Samuel Ketcham, who along with relatives Abijah, James, Daniel, and William Ketcham, was listed as a 14th Albany County Militia soldier, was listed as the collector. John Knickerbacker and Harman Groesbeck of Schaghticoke along with residents of future Pittstown Wendel and Michael Overacker, Thomas Halstead, and Joseph Gifford signed the paper as those ordering the donation. Those on the list of donors of stockings included Michael Overacker himself, along with ten others, and the five donors of shoes included Michael Cook, Jr., (Michael Vandercook), eldest son of the original Michael, founder of Cooksboro, and Henry Vanderhoof, one of the Captains of the 14th.

In October of 1779, the fledging Legislature of the State of New York assessed the property value of all landowners, preparatory to taxation, aiming at raising $2,500,000 statewide. The military had to be outfitted, fed, and paid, government officials at the local, state, and national level compensated for their time and travel.

Another rare survival in the archive of the town of Schaghticoke is a “class list” of 26 local militia men. The whole US militia was divided into classes, which would be required to outfit one of their own to go into the regular army. The men in this Schaghticoke list from 1782 were required by their Colonel, Peter Yates, to provide an “ablebodied man equipt for the field…to be delivered at Saratoga where he will be mustered without delay.” The 26 men would provide money and/or equipment for the one among them who would go to serve.

The next task of each new state was to assemble the militia. There were experienced soldiers among the residents of Schaghticoke, thanks to service in the militia in the French and Indian Wars. The laws of New York required that every male between the ages of about 18 and 45 be members of the militia, subject to being called to duty as required. (Indeed, a similar law is still in place in the US.) The 14th Albany County Militia was the unit that encompassed the Schaghticoke and Hoosick districts. On October 20, 1775, John Knickerbocker was appointed the Colonel of the Regiment, which included forty-six officers and 684 men, about 140 of whom were from Schaghticoke. They were divided into seven companies and a company of “Minute Men,” who presumably would be called on first in an emergency. We know the names of many of the men who served in the 14th Albany Militia, thanks to published compilations of records of the New State of New York. . When the men were called to duty, they would have worn their own clothes and brought their own weapons. One of Colonel Knickerbocker’s tasks was to obtain ammunition and food for his men.

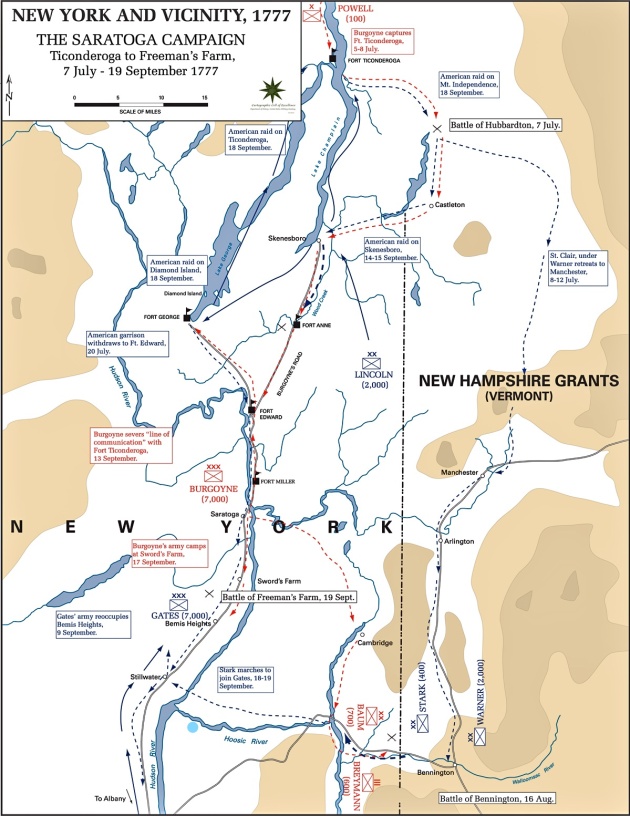

Unlike many citizens of the new U.S., people in Schaghticoke would have been worried about British invasion from the start. Lakes Champlain and George and the Hudson River were an obvious invasion route in both directions. The first campaign of the new U.S. Army was to invade Canada. General Phillip Schuyler, our neighbor across the river in Schuylerville, and indeed a property owner in Schaghticoke, bought 23 ¾ tons of hay here in February, 1776, hauled by 57 sleds to Fort George on Lake George. Local citizens must have been eager to do their part, especially after the invasion of Canada failed, and the British took Fort Ticonderoga in July 1777.

We know about the service of the militia during the war because some of the members of the local militia lived long enough to be able to apply for Revolutionary War pensions. Indigent veterans were first eligible to apply in 1818, and many more applied under a law in 1832. In order to receive a pension, the men had to prove and detail their service in the war. As virtually none of them had received any paper confirmation of service, they had to testify at length about their service. I have read the pension applications of at least a dozen members of the 14th, and while the details differ, depending on what company the man was in, they all record having been called out to serve once or twice a year from 1775 to 1782, for two to six weeks at a time. We have to remember that these men were writing at least thirty years after the events occurred, and as old, poor men, probably with imperfect memories. On the other hand, being in a war would certainly be a memorable experience. They served in Saratoga, Ft. Edward, Sandy Hill (Hudson Falls), Ft. George, Skenesborough, and other places in this general area. They mostly garrisoned and built forts and breastworks. Several participated in the battle of Bennington, in August of 1777. Of course, they had to walk everywhere they went, something to think about when imagining their service.

It must have been very disruptive to these men, mostly farmers, to be called out unexpectedly over such a number of years. Apparently the commander would call for volunteers among his militia company. If enough men responded, fine, if not, more would be required to serve- or be drafted. My view of militia men has always been that they were an essential part of our winning our independence from Britain, but Phillip Schuyler did nothing but bad-mouth them in his letters. They were unreliable, ate too much, stayed for indeterminate periods of time, didn’t work hard enough, and had no training.

Local men had differing experiences in the 14th Albany, depending on when they volunteered or were drafted and which company they were in. One example is Jacob Yates. Yates was born in 1754. He married Elizabeth Vandenberg in 1776 at the Dutch Reformed Church in Schaghticoke and entered the militia the same year. John Knickerbocker was his first Colonel, but his second was his father, Peter. Yates rose through the ranks to be a Captain by 1780. He served to the end of the war, travelling many times to Fort Edward, Ballstown, Ticonderoga, and Crown Point, and twice to Montreal. His children applied for his pension after his death at age 77 in 1831 in Schaghticoke.

Solomon Acker left a more detailed account. Acker was born in Dutchess County in 1753. He entered militia service in May 1775 in Captain Hicks Company of the 14th in Schaghticoke. During that year he was “employed in watching hostiles and Tories at Schaghticoke.” This confirms the account of Beth Kloppott in her History of Schaghticoke, that at the start of the war, the 14th Albany County militia men were called out to guard the district from loyalist activity. I think this was a task of the militia through the whole war.

Early in 1776, Acker was ordered to Albany, and served there and in Johnstown, but he returned to Schaghticoke and a new company in the 14th in June. At the time of the battle of Saratoga in 1777, Acker states he and his company guarded provisions on the east side of the Hudson at Stillwater. He was involved in another major incident at the time, which I will describe elsewhere. Another soldier, Cornelius Francisco of Pittstown, reported the same duty. On the other hand, Wynant Vandenburgh, in the Company of Captain Jacob Yates (mentioned above), worked all the summer of 1777 moving artillery of the army from Fort Edward to Stillwater, and then to Half Moon, ahead of the advancing British General Burgoyne and his army. That must have been very difficult work indeed. Vandenburgh was home briefly, but then in early October was in the “first battle and the capture of Burgoyne.” His timing is a bit off, as the first battle was in September. Apparently, Colonel Knickerbocker was wounded or injured at this time, with Colonel Peter Yates, also of Schaghticoke, taking his place.

In 1778 Solomon Acker joined the company of Jacob Yates and went with a scouting party to Fort Edward. Acker doesn’t report any other service in the war, but Cornelius Francisco of Pittstown does. He volunteered in both 1778 and 1779, travelling to Fort Edward, guarding the frontier. In June of 1780 he marched to Fort George with Colonel Yate’s regiment. Governor George Clinton was there, ready to lead an expedition in pursuit of Tory leader Sir John Johnson. Francisco volunteered to go, and the expedition crossed Lake George in bateaux. He was “out on this tour one month.” Another 14th Albany veteran, John Palmer of Hoosick, reported ending up in the “life guard of Governor Clinton” at the time, serving for six weeks. He gave the year as 1782. Cornelius Francisco also volunteered for a couple of weeks in 1781 and 1782, going to Ft. Edward, Ft. Miller, Saratoga, Sandy Hill, and Skenesborough. Another soldier, John Palmer of Hoosick, participated in the battle of Bennington, then went on to guard the provisions at the time of the battle of Saratoga. The long Revolutionary War period was certainly one of danger and upset for many local families.

I found the idea of the Governor of New York, George Clinton, leading expeditions against the Tories astounding. Imagine Andrew Cuomo putting on a uniform and leading the National Guard on an expedition against an enemy. John K. Lee, in George Clinton, reports that Sir John Johnson commanded a force of Tories and Indians on raiding expeditions from Montreal to the Mohawk River just west of Schenectady in 1780 and on Lake Ontario to Oswego to Schoharie in 1781. Governor Clinton, who began his public career as a commander of militia units south of Albany on the Hudson River in 1775, personally commanded the militia which pursued Johnson both times. The reports of the veterans of the 14th Albany are probably true, even if their timing may be a bit off.

Throughout the war, Schaghticoke was near the northern border of the new United States, with the residents afraid of raids by British, Tories,and Indians from British Canada. But the war really came home to Schaghticoke in the summer of 1777. As General Burgoyne and the British army advanced south from Canada, residents of Schaghticoke became more and more worried. In July they would have heard of the murder of the whole Allen family of Argyle and of the murder and scalping of Jane McCrea of Ft. Edward by the Indian allies of Burgoyne’s Army. The American General Gates sent a letter to Burgoyne in August accusing him of hiring Indians specifically to murder Europeans, paying them a bounty for each scalp. Of course the legend, and perhaps the truth, is that the murder of Jane McCrea became a rallying cry for the American troops leading up to the battle of Saratoga, inspiring many militia men to join the fight. Whether this was true or not, people in our area would have been getting more and more scared for themselves and their property.

Many families from Schaghticoke and all around evacuated to Albany. Perhaps Lansingburgh, a small village at the time, was the first destination. As Troy did not yet exist, Albany was the first large settlement. It would have taken some time to reach Albany, either by water, having to get around the falls at Troy, or by trail- no Routes 40 and 787! General Gates made a special offer to the men of the evacuated families to join the Continental Army, to be provided with the usual rations “for themselves and their families,” in part because the number of refugees was proving too large for Albany to accommodate.

Our local Gothic author, Ann Eliza Bleecker, was among the evacuees, suffering the tremendous trauma which fueled her later writing. She and her family continued on down the Hudson to Red Hook, where they had relatives. It was certainly terrifying and wrenching for all of the evacuees, leaving their homes, animals, and crops to who knew what fate. Finding housing would have been difficult. Did they take their cows with them? Did they try to take their most precious possessions? Sylvester’s History of Rensselaer County reports that the Viele family, living on the Tomhannock Creek in the Albany Corporation area, buried some of their belongings in a ravine.

In August and September of 1777, some of the more enterprising local farmers arranged to sell their crops and flour to the Continental Army, based at Saratoga, taking advantage of a market that was sure. Certainly the Army would have been seeking them out at the same time. Some of the American troops were camped in the Schaghticoke area, and after the war some residents petitioned the state for compensation for the fences destroyed for firewood and crops taken by the soldiers. One document in the NYS Archives records the claim of Daniel Shaw, who claimed loss of bushels of corn to the troops of Colonel Yates in 1777.

Other crops were evidently destroyed by marauding bands of Tories and Indians, and one source says that one of the few grist mills in town was burned by the Tories. In The History of the Seventeen Towns of Rensselaer County, the author quotes a “patriotic member of the Knickerbacker family” as stating in 1876 that at the time of the battle of Saratoga “the ancient fort or block-house was taken possession of by a troop of Hessian soldiery, in the service of the British,” who raided the homes of the neighbors. French’s” Gazetteer” of 1860 states, “at the approach of Burgoyne, through the influence of royalists, the place was not burned, though it was held for some time as an Indian and Hessian outpost.” (p559)I truly doubt these two stories as there were so many American soldiers in the area. The local regiment was based at the river crossing at Stillwater, and there were New Hampshire Continental troops here in early August, as I will discuss below. One source says that troops of the American General Lincoln were camped at Schaghticoke before the battle, meaning the Hessians certainly wouldn’t have been in the fort. This, however is questionable, as Lincoln didn’t take command in the area until after September 22.

There is no doubt that there were bands of Tories, Indians, and perhaps Hessians and British roaming through the area during the summer of 1777 before the battle of Saratoga. The tombstone of Michael Vandercook (1715-1786), member of the local Committee of Correspondence and grist mill operator in Pittstown, records : “The above sage was a firm friend to the liberties of this country in 1776, by which he lost the better part of his prosperity, and in July 1777 he had his home robbed and his life threatened by some of the British King’s robbers while his sons and the rest of the military were gone to the Northward to oppose Burgoyne, as also by the depreciation of the then currency, all of which he bore with Christian fortitude.” This puts the local problems in a nut shell. The tombstone is in the Old Cooksboro Cemetery, translated by a contributor to Find-a-Grave.

thanks to find-a-grave Michael Vandercook’s tombstone

The most famous story concerns Major Derrick VanVeghten and his aide, Solomon Acker, whom I already discussed above. This story was told by Acker and others, and recently, a gentleman named Charlie Frye, who has a blog called “Duty in the Call of Liberty,” wrote to tell me of a narrative of New Hampshire soldier Joseph Gray, included in the “History of the Town of Wilton, New Hampshire,” published in 1888, but recorded in 1839, which relates the same story and adds to it.

As a youth of 16, Gray marched as part of the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment to Ticonderoga in May, 1777. They retreated before the British General Burgoyne down the Hudson Valley, destroying bridges to slow the British advance. Once they reached Stillwater, about the beginning of August, a detachment, including Gray, was sent to Schaghticoke, “a small Dutch village.” This would have been the settlement around the Knickerbocker Mansion- where there was a church- near the junction of current route 67 and Knickerbocker Road- and a small log fort. The “inhabitants being alarmed at the appearance of savages who were lurking about, sent for a detachment of troops to guard them off.” As I wrote above, the local militia men were either assigned to guard supplies at Stillwater or help move artillery from Fort Edward to Stillwater at this time. If the 14th Albany Militia had been at Stillwater, one might think they would have been able to return to help their families, but perhaps not. They were in the Army, after all, and subject to orders. Hence the need for the New Hampshire men, who were Continental regulars rather than militiamen.

Residents of the farms from the area had gathered together for safety. Gray was on guard that night, sitting near the Dutch Reformed Church, “on a beautiful level plain,” now the Weir Farm. If the men saw anything moving they were to yell, then if they got no answer, to shoot. They had been told that the Indians were wearing “white frocks”, probably long, loose linen jackets. He saw something white coming towards him in the starlight and shouted, “Who comes there?” No answer. After three hails, he fired, and found he had shot a “meager white faced bull.”

The next day, two of the local farmers, among those gathered near the church, rode their horses to their farms, “about ¾ of a mile distant,” to get some provisions. The soldiers soon heard “the well-known report of Indian fusees (muskets), and were much alarmed for the safety of the men.” One of them soon rode in at full speed, calling for help. His friend had been shot and scalped, his throat cut. The New Hampshire commander, Major Ellis, called for reinforcements, and the militia men escorted the villagers four miles down the river “to a place of safety,” presumably Lansingburgh. Gray went on to fight in the battle of Saratoga, then on to other battles of the war with his militia.

In 1840, Gray’s narrative was published in a magazine in New Hampshire, “The Farmers’ Cabinet.” A resident of Schaghticoke, Mr. B.A. Peavey, wrote to the magazine in reply. Peavey was inspired by the article to speak to elderly residents of town to see if they knew of this incident. Amazingly, Peavey reported speaking to Major Vanvecton(sic), “aged between 70 and 80”, who remembered the man shot by the Indians. “His name was Siperly;” “the man who came riding back was Old Poiser.” VanVecton even showed Peavey where Siperly had fallen, on the “bank of the Tompanock Creek, where a point of the hill presses the road close to the creek.”

He added that “immediately after the death of Siperly, Major Knickerbocker of the settlement sent his negro to the North River…where some of the neighbors were engaged in placing their property aboard of boats to secure it from the enemy.” Major VanVecton’s father and Solomon Ackerth (sic) started for the settlement. They were shot at by Indians, and “Vanvecton received two balls in his thigh, which passed through his tobacco box in his breeches pocket, and he fell…Ackerth shot one Indian and killed him…took VanVecton’s gun and wounded another.”

Major VanVecton had preserved the tobacco box with the bullet hole. His father had lived just to the south of the Dutch Reformed Church. Another informant, “Black Tom,” presumably an African-American, was 12 at the time and told Peavey he remembered the bull being killed.

Certainly, this account emphasizes how dangerous it was in Schaghticoke in summer 1777. Besides confirming the death of VanVeghten, it adds the death of another man. It also makes it seem that Derrick VanVeghten and Solomon Acker went to check on the beleaguered citizens of Schaghticoke, probably including their own wives and small children, rather than just checking on VanVeghten’s property.

Let’s look at the account bit-by-bit. First, as to the man writing the letter to the “Farmers Cabinet,” there was a Benjamin A. Pevey living in Schaghticoke in 1840. In the 1850 US census, he was a 54-year old laborer, with a wife and many children. He moved to New Hampshire by 1860 and died in Massachusetts in 1864. Second, as to the “Major Vanvecton” who was the informant, I feel this was John, son of the man killed, Derrick VanVechten. John was born in 1773 and lived until 1860 in Schaghticoke as a wealthy farmer. He did serve in the local militia, though I cannot find he was a Major- perhaps there was an exaggeration of his rank. But he could have been Pevey’s informant.

As to the man who died, Siperly, there was one Sipperly, Jacob, on the roster of the 14th Albany County Militia, but he survived the war. But there were other Sipperlys in town. “Old Poiser” could be Piser, I suppose, and there were Pisers in town early on. For example, a Christian Piser is buried in the Lutheran Church in town. He died in 1800 aged 77. There are just not death records, newspapers, nor surviving tombstones from that era. Plus, Sipperly and Piser were Lutherans, who lived in the Melrose/Pittstown area, so would they have been over near the Dutch Reformed Church? Perhaps they too had moved to what was then the town center for protection? We just won’t know, I think.

Returning to the letter, of course, there wasn’t a Tompanock Creek, but Tomhannock, so we know there was an error here. But the Tomhannock is close to the road along Buttermilk Falls Road today, where there is a hill on the east side, making the location a possibility. It is also interesting that Major Knickerbocker’s “negro” was sent to the North River- this was certainly the Hudson River- and the North River was another name for it. He was actually Colonel Knickerbocker, a higher rank. The VanVechtens did live just south of the church. And finally, “Black Tom” , who remembered the incident with the “murder” of the bull, was certainly Thomas Mando, who began life as a slave of the Knickerbockers, born about 1767, and lived on in town until at least 1850, when he appeared in the census at age 83. So it seems that much of this account is possible, and perhaps probable.

It also confirms the story that Solomon Acker himself told. Acker, who lived until almost 1850, told the story through his whole life. It also appears in Sylvester’s “History of Rensselaer County,” published in 1880. In his Revolutionary War pension papers, Mr. Acker states he was with Major VanVeghten at Schaghticoke in July 1777 when VanVeghten was “shot by the Indians,” and that Mr. Acker killed one of the Indians himself. He states, “Immediately I raised a guard and warned the inhabitants, and assisted them in removing to Albany.” So Solomon adds to his role.

Sylvester, in his History of Rensselaer County sets the event in August, and describes the area as deserted, as everyone had already evacuated to Albany. He states the men were on the land of Jacob Yates, (which was on the Hudson River north of the junction with Pinewoods Road) when “they were fired upon by Indians or perhaps Tories.” He adds that VanVeghten was shot through the tobacco box, which was handed down in his family, and that the Major, realizing that he was mortally wounded, yelled, ”Solomon, take care of yourself; you cannot save me.” Acker fled reluctantly, “with the bullets pattering around him,” reaching the Army safely. Mr. Acker told this story, apparently much embroidered from the version in the pension papers, to two local men, who told it to Sylvester. They even pointed out the spot on the farm of W.V.V. Reynolds where the murder occurred. This was probably near the intersection of Farm to Market Road and Howland Avenue Extension.

A memoir written in 1866 by John P. Becker, Sexagenary, Reminiscences of the American Revolution, really takes the story to fiction, describing the circumstances of each shot taken by VanVeghten, Acker, and the enemies, going on to describe Acker’s flight step by step, and stating that when the Americans went to retrieve VanVeghten’s body, they found “him hacked to pieces and scalped, and…three Indians dead in an adjacent field.” It also places the event as occurring after the battle of Saratoga. Who knows if Mr. Acker told the story this way or if some source of Becker added to it? The memoir states that Van Veghten was buried in Albany, but “his unfortunate wife was not permitted to see the corpse, it was so savagely mutilated.”

In doing more research as a result of reading Gray’s account, I found that there was lots of confusion about the murder of VanVeghten in the Van Veghten family itself. “Genealogical Records of the VanVeghten Family”, by Peter VanVeghten (1900) tells a wildly inaccurate version. In this version, Major Derrick was part of a group including a Colonel Solomon Acker, that pursued the party of Indians and Tories who had murdered Jane McCrea near Fort Edward. As you may remember from middle school, Jane McCrea was the fiancée of a Tory soldier in the British Army and was killed and scalped by Indian allies of the British while being taken to him on July 27, 1777. Her fate was one of the rallying cries which brought American militiamen to fight at the battle of Saratoga.

This VanVeghten story promotes Solomon Acker to a Colonel, includes a wild image of the tobacco box, labeled “Major Derrick VanVeghten 1777”, which it states is in the possession of Henry C. VanVechten of Racine, Wisconsin, a great-great grandson. It adds a quote from the “Troy Telegram” of July 21, 1882: “the bones of Lieut. VanVechten were accidentally exhumed at Fort Edward yesterday by workmen…VanVechten was a soldier…and was killed while in pursuit of the party who murdered Jane McCrea. He was buried on the brow of the hill near the spot where he fell…the ball was still in the skull when found.” It seems this story really is about a Tobias VanVeghten, who was a Lieutenant in Colonel Goose VanSchaick’s Batallion, the 2nd NY Regiment in the Continental Army. Tobias and some others were based near Fort Edward and were attacked by a group of Native Americans who were rampaging in the area and were probably those who killed Jane McCrea as well. So this happened on July 27, 1777. Tobias was buried near the spot where he fell.

The inaccurate story in the VanVeghten genealogy also appears in “The Spirit of ‘76”, written in 1896, as a part of a longer article about VanVeghten family and memorabilia, and completely shifts the story from Schaghticoke, to a Derrick VanVeghten who has now become a Major in the Tryon County militia regiment of Cornelius VanVeghten, with Colonel Solomon Acker. The tobacco box remains but now is pewter. There was a Lt. Col. Cornelius VanVeghten, but he was with the 13th Albany County Militia. I have found no Colonel Acker. One possible source of the some of the confusion could be that the death of Major Dirck VanVeghten of the 14th Albany County Militia on August 8, 1777, is reported in a list of casualties in a Tryon County regiment at Oriskany on August 6 (Documents relating to the colonial history of the state of New York vol XV, Albany 1887- appendix, p 549). Indeed, a photo of the tobacco box was exhibited at a World’s Fair in Wisconsin in 1893, labelled as from Major VanVeghten, who died at the battle of Oriskany.

Putting together various sources,I can conclude that the great article in the Wilton history confirms the very dramatic story of Major Derrick VanVeghten and his aide Solomon Acker riding near the Denison Farm on Buttermilk Falls Road on August 8, 1777, when they were set upon by a few Indians. The Major was shot, killed, and scalped. Acker escaped and returned with help to retrieve his body- and his tobacco box- . It adds the information that another local man was murdered the day before and that the settlers of our little town were evacuated to Lansingburgh with the help of the New Hampshire Regulars. I guess it is possible that Solomon Acker helped with the evacuation, but the New Hampshire men were there, and he certainly didn’t organize the evacuation. And all of this certainly happened in August. I don’t think we will know where the murder of VanVeghten occurred exactly, certainly somewhere near the Knickerbocker Mansion.

Major VanVeghten’s wife, Alida Knickerbocker, lived on until 1819; his son John inherited the local property and reported the events in 1840. Solomon Acker lived in Schaghticoke until 1836, when, at age 83, he moved to Connecticut to live with his son David. He is recorded there in the 1840 census, listed as 90, but died before 1850. The tobacco box was in Wisconsin in 1894, but now??? Whatever the truth of this particular incident, it confirms the danger in the area during that summer of 1777.

The 14th Albany County Militia was certainly called to duty during the summer before and through the time of the battles of Saratoga. This means that many families were evacuated from home and had to survive without their husbands and fathers, though they may have had help from some militia men during their evacuation. In addition, most people were away from home at harvest time. After the battle was over, about 6000 British and Hessian prisoners of war were evacuated to Boston, probably crossing the Hudson in boats or over a bridge of boats at Stillwater, and passing through the town of Schaghticoke. This probably resulted in more damage to fences and farms.

I find it difficult to look around our town now and imagine it on the edge of the battle that was the turning point of the Revolution, to imagine how I would feel if I were forced to evacuate my home, how I would feel to return home and find my property in ruins.

We now consider the Battle of Saratoga “the turning point of the Revolution,” but at the time, it didn’t change too much for people in this area. Until 1782 there was a continual concern of a new British invasion from the North, or at least for raids by British and Tories. Messengers from the British in Canada travelled to the British in New York City the whole time. In 1780-1781 there were attacks on Fort Ann, Saratoga and the Ballston District, and White Creek.

Perhaps the most frightening event for Schaghticoke occurred in early August 1781. Major John McKinstry, commander at Saratoga, wrote to Phillip Schuyler that a Loyalist named John Jones and others had an “intention to make prisoner of a number of the principle inhabitants near this place as proof of which they have taken Esquire Blaker (John Bleecker) of Tomhannock last Friday.” The order came from British commander Colonel Barry St. Leger. This was John Bleecker, husband of novelist Ann Eliza Bleecker, kidnapped and taken to Vermont, where he was freed by citizens there. This was just the prelude to the attempted kidnapping of Philip Schuyler himself a few days later by a different group. On August 7, a band invaded Schuyler’s home in the city of Albany and kidnapped two of his guard, though Schuyler and his family evaded capture. We may feel that the U.S. victory at the battle of Yorktown in October, 1781, ended the war, but not in our area. Danger persisted, partly due to the controversy over the border with Vermont and the Hampshire Grants.

Schaghticoke was in the thick of the controversy over the land that would become the state of Vermont in 1791. As of 1750, three colonies claimed Vermont: Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York. In 1764, King George proclaimed that the area that would later be Vermont belonged to Albany County, New York. New York surveyors began to set up counties in areas which had already been surveyed by New Hampshire. Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys formed to fight for an independent Vermont, either as a state or its own country. They claimed the territory of New York west to the Hudson River and between Canada and Massachusetts. This, of course, would include Schaghticoke. Settlement of the controversy was delayed by the Revolutionary War, and the Green Mountain Boys not only fought the British, but raided as far as Schaghticoke, trying to establish the western boundary of Vermont as the Hudson River. British commander Colonel Barry St. Leger held secret meetings with the Vermonters, trying to incite them to rebellion against the new nation.

In May 1781, a Convention was held in Cambridge which repeated Vermont’s land claims. Representatives were from many supposedly New York communities, including Hoosick, Saratoga, Fort Edward, and…Schaghticoke. But as the threat from the British waned, many at the convention renounced their support of Vermont. They had been afraid that the Green Mountain Boys would destroy their forts, leaving them defenseless.

The events of the following summer were chaotic. According to Kloppott’s “History of Schaghticoke,” Colonel Peter Yates and the 14th Albany County Militia garrisoned the old fort at Schaghticoke. They were to be ready to put down any rebellion or unrest against New York by the Vermonters. According to John Kaminski in his biography, George Clinton, Governor of New York was rightly concerned that the Vermonters and the British would join together to attack frontier sites, such as Schaghticoke. About sixty residents of Schaghticoke met that summer to elect representatives to the assembly of Vermont! Two local men even acted as justices of the peace for Vermont. And both local residents and people from uncontested Vermont even tried to force others to support Vermont. A notice was sent by New York to Schaghticoke residents warning them to “Cease from all seditious..conduct.”

In August, the governor of Vermont, Thomas Chittenden, wrote to Colonel Yates, berating him for “drafting and forcibly compelling sundry Inhabitants on the East side of the Hudson into the service of the State of New York…creating disregard for the Jurisdiction of this State” (Vermont). In other words, Chittenden felt Yates had no right to call out his 14th Albany County militiamen in Schaghticoke and Hoosick, as they were living in what he claimed was Vermont. Colonel Yates responded that he had taken an oath to serve New York State, and needed to obey his orders- which were to assemble his militia men to protect the area from raids by Vermonters.

Matters reached a head in December of 1781. Lt. Colonel John Van Rensselaer, Colonel Bratt, and others of the 14th Albany were taken prisoner by “tirannical Ruffians who have disavowed allegiance to the state of New York”. This was a mutiny within their regiment. Some of the men who had served together throughout the Revolution were now changing allegiance from New York to Vermont. They went so far as to kidnap their officers. They were taken to Bennington, where they “were treated in a most scandilous manner” before being released. It is unclear why any of these people were kidnapped. Maybe the mutineers had some thought of forcing them to swear allegiance to Vermont.

General Gansevoort ordered Colonels Yates and Henry VanRensselaer to march the loyal men in their regiments to the aid of Lt. Col. John VanRensselaer at his dwelling in St. Croix or SanCoick- near present day Hoosick Falls., and “to take such measures for quelling the Insurrection as shall appear necessary and expedient.” The General added, “I must recommend to you the greatest precaution and Circumspection in the Matter.” That seems a tall order- quell an insurrection, but be careful. General Stark added his opinion, telling Yates that the insurrection “must be the result of folly and madness. You will be very cautious not to begin hostilities with them but stand your Ground and act defensively until reinforced.” The whole thing was very upsetting: the Revolutionary War not even over, yet fighting was beginning within the new States. And no one wanted to begin shooting at former comrades.

Colonel Yates reported to General Gansevoort from St. Coick on December 12. He said he only had 80 men, and the insurrectors 146. The “rioters” were in a block house, which Yates could not hope to take as he had no artillery. He did not want to back down until the matter was resolved as “we shall all be taken immediately by the other party and be obliged to comply to their will.” Yates asked for artillery and reinforcements, and concluded “the men is (sic) very uneasy wanting either to fight them or go home.”

General Gansevoort came out in person from his headquarters at Saratoga to lead the militia, arriving at the house (inn) of Charles Toll of Schaghticoke at the same time as the sheriff of Albany. The sheriff arrived with a warrant to arrest some of the insurgents. Toll’s house was at a bridge over the Hoosick River, perhaps where the bridge at Valley Falls is today. Before this group could head for Hoosick Falls, the retreating militia arrived. They were being pursued by “the militia of the pretended State of Vermont, consisting of at least 500 men with a field piece (a cannon)”. General Gansevoort led a further retreat, “to the town of Schaghticoke, where the Men might be housed from the inclemency of the cold weather,” and in a more defensive position. The General does not say so, but perhaps this was in the old fort at Schaghticoke, near the current Knickerbocker Mansion. Discretion being the better part of valor, the General dismissed the militia, as reinforcements were not arriving, and with 80 men he couldn’t hope to prevail against 500. He stated that the residents of Schaghticoke, “especially those who have taken an active part against the insurgents, are in a very precarious Situation.” They were afraid they would have to either swear allegiance to Vermont or abandon their homes.

In any event, everyone settled down, unwilling to have war between new Americans. The majority of people in Schaghticoke remained loyal to Albany County and the state of New York. Vermonters decided to take their case to the Congress of the new United States and seek a legal settlement. This didn’t happen until 1790, when New York paid Vermont for part of the disputed land. Obviously, Schaghticoke remained in New York, but if the militia on either side began shooting, who knows what would have happened?!

Bibliography:

1779 list of shoes and stockings, Town of Schaghticoke archives

1782 Class list, Town of Schaghticoke archives

Becker, John P. Sexagenary, Albany, Munsell, 1866.

Fitch, Dr. Asa, Their Own Voices, reprinted 1983.

Gerlach, Donald, Proud Patriot, Syracuse U. Press 1987 p 120, 458

Kloppott, Beth, History of Schaghticoke, 1980.

Kaminski, John, George Clinton, Madison House Publishers, 1993.

Lee, John K., George Clinton, Syracuse U. Press, 2010.

Minutes of the Committee of Correspondence

Minutes of the Commission on Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies

Public Papers of George Clinton, Vol 7; NYS, 1900

Roberts, James, NY in the Revolution as Colony and State, 1898.

Sylvester, Nathan, History of Rensselaer County, 1880.

Various pension papers in Heritagequest.com

: