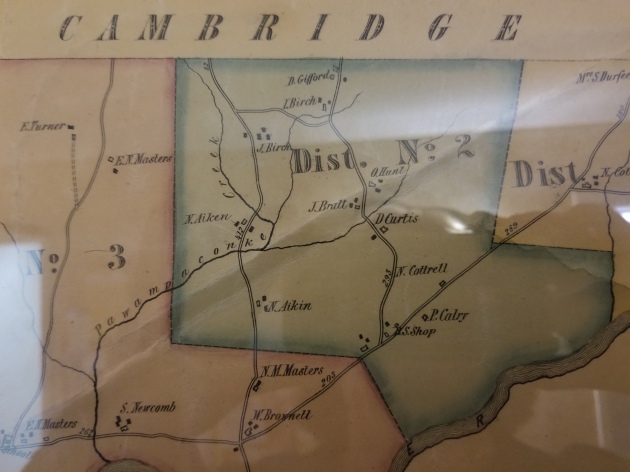

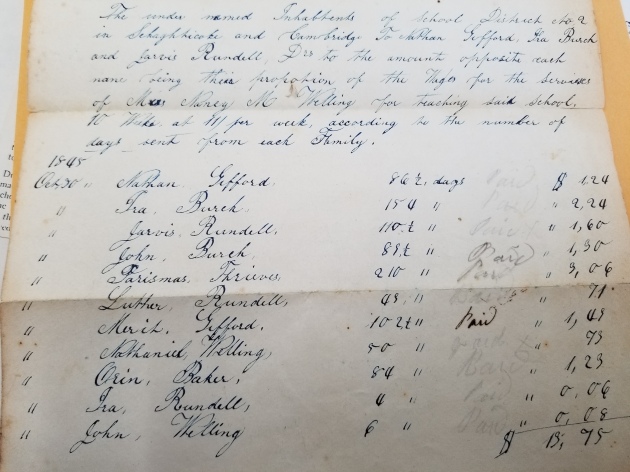

Honestly, I am biding time in my column. I am just about finished with a long piece about Schaghticoke around 1900- at this point about 50 pages long- but it’s just not ready yet. So I have been sharing bios of local men who fought in the Civil War. These were written a few years ago and have not been published. I was prompted to share the story of Henry J. Simmons as a good friend just told me the version of his early life that he had heard. I have heard much of what he told me too, and feel it is a tall tale, though much more exciting than his real life. I think I can set the record straight, though it will take a couple of columns to do it.

Henry Simmons was born in Canaan, Columbia County on March 8, 1831. I can’t find him in the public record before the Civil War, but I believe I found his parents in the 1850 US Census for Canaan: Charles, 55, and Harriet, 50, Simmons, plus a daughter Dorsey, age 19. Charles was a laborer with a personal estate of $400. I’m quite sure this is the correct family as Henry and his parents were free blacks, and certainly in a real minority both in Columbia County and here. I haven’t found Henry in the census that year, however. All blacks were free in New York State after 1828. Many freed slaves moved away, though not the Simmons.

I sent to the National Archives for Henry’s Civil War pension file, and it provided lots more information. He married Julia Jackson in 1852 in Rochester, NY. Julia was working in the hotel of John Schriver in Kingston as of the 1850 U.S. Census, when she was 18. They had three children born before the war: Daniel in 1854, Richard, in 1856, and Julia, in 1860. Henry was also unusual as a free black with a wife and family. Most were individuals, either black barbers or black cooks or serving maids in hotels.

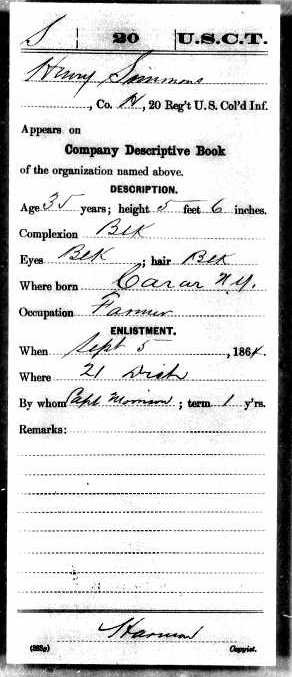

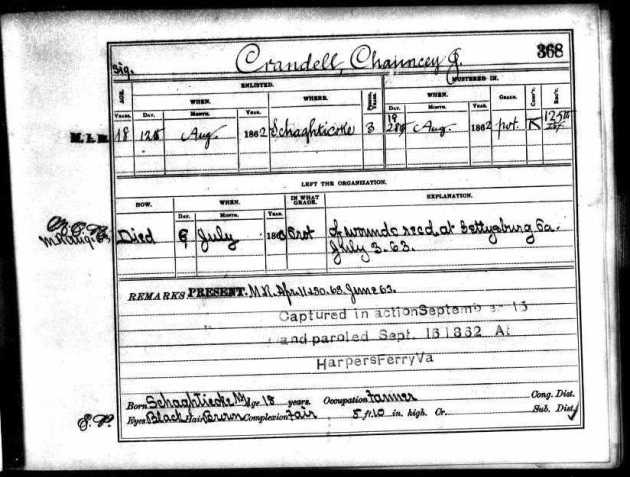

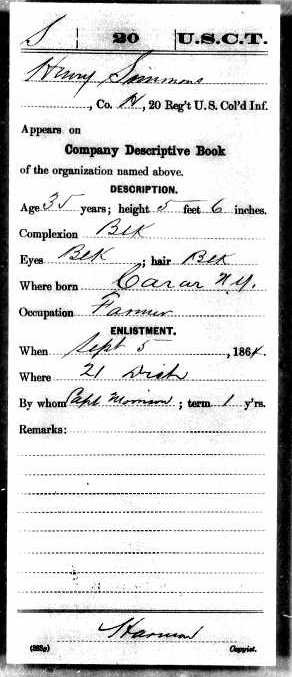

On September 5, 1864 Henry enlisted in Company H of the 20th U.S. Colored Infantry. The regiment had been formed at the end of the year before, in response to the desire of black men to serve in the Civil War following the publication of the Emancipation Proclamation, and the need of the Union army for more men. It mustered on Rikers Island in New York City. Shortly after formation, it went to New Orleans, where it served through the end of 1865. Only one enlisted man died in combat, but 263 died of disease out of the regiment of 1000 men.

Henry gave his age as 35 when he enlisted. He was 5’6” tall, and gave his occupation as farmer. He gave his birthplace as Canaan, New York. Henry mustered out after one year of service, with the rest of his regiment, in September 1865.

I know from Henry’s pension file that he was in an Army hospital for some months in 1865, suffering from jaundice. He also told a long and detailed story about receiving an injury to his right foot. While in the hospital, Henry had improved a bit, and a doctor asked him to hold the horses of his carriage. He and his wife were going to go for a drive. The flies were bad and one of the horses swiped at flies with its back foot, which it put down directly on Henry’s right instep. He ended up back in the hospital, still ill, but now with a badly injured foot. Henry was discharged from the hospital but never really returned to duty and walked with a limp thereafter. After a few years, his foot began to break open and drain yearly, for the rest of his life.

After the war, Henry lived in New York City for a few months, then in Albany for a few months more. He moved back to New York City in the fall of 1866 and lived there until 1872. He was coachman for a W.P. Furness. In 1873, he moved to Schaghticoke. I know these movements from Henry’s pension file, but don’t know where his family was during all of these years, nor why he moved around.

The first time I can find Henry in the census after the war, he and his family were living in the village of Schaghticoke in 1875, with Henry listed as a laborer. I wonder if he came here because he had heard of Schaghticoke from Amos Vincent, a local man who was a fellow soldier in Company H. In the 1880 US Census, Henry and wife Julia, 43, listed children Cordelia, 15; Emma, 13; Isadora, 6; and Harry F., 10 months old, in their family. Henry had a good-paying but dangerous job in the gun powder mill; Cordelia and Emma worked in the woolen mill.

From the records of Elmwood Cemetery, I know that Henry and his wife had had a younger son named Harry, born in August of 1875, who lived just 9 months. The Harry born in 1879 died at age 11. And the cemetery records give Henry’s wife’s name as Candis Julia Jackson. She was born in 1837 and died in 1887 of pneumonia.

Henry applied for a Civil War pension in 1885, before they were available on the basis of old age. His claim was based on his foot injury, and was rejected. Several of his fellow soldiers testified about the circumstances of the injury, but their descriptions were contradictory. And the Army’s hospital records showed he was only hospitalized for jaundice, not for a hurt foot.

But several local people testified as to his disability. These neighbors, Herbert H. Dill, John Healy, and Nelson Viall, all stated that Henry was a man of good character, a hard worker, who lost a couple of months of work each year due to his foot injury and used a cane or crutches often. His local doctors, W.C. Crombie and D.H. Tarbell, described the injury in great detail. Dr. Tarbell, a fellow veteran, added that Henry now had kidney problems in addition to the foot injury. Dill and Healy were also veterans.

In 1890 he began to receive a $6 per month pension just based on old age. Henry applied for more money in 1896, adding in the foot problems again, and did get more at that point. Of course he appeared as a widower in the 1900 US Census. Now 69, he was still a powder maker, living in the village. His daughter Cordelia, now 34, took care of the house, which included her sisters Isadora 24, working as a twister in the woolen mill, and Maude, 19, who was a servant. Maude had been born in 1882, so lost her mother at age 5.

A surgeon’s certificate in the pension file describes Henry in 1898, aged 67: 5’10” tall, 145 pounds, in fairly good health except for his right foot, but with no teeth except for a few stumps. The doctor felt he had some heart problems which led to his shortness of breath, plus some rheumatism.

Three little granddaughters, Ruth Lovelace, born in 1889, and twins Edith and Edna, born in 1892, lived in the family in 1900 as well. They were the daughters of Henry’s other daughter, Emma, who had married Edward Lovelace. Emma died of heart disease at just 25 in 1892, leaving the three little girls. Edna died in 1907. The father of these girls was not far away. As of the 1900 census Edward Lovelace lived in a rooming house in Troy, and worked as a porter. Presumably he lived in Troy for work. He was also black, born in New York in 1860. His parents were born in Florida. It is interesting to speculate how they ended up in New York in 1860 if they were slaves in Florida. Edward died of tuberculosis in 1915, and is also buried in Elmwood.

The 1910 US Census listed Henry on West Street in the village of Schaghticoke. Now 79, he was retired. His daughter Cordelia, 44, was still keeping house. Granddaughters Ruth, 20, and Edith, 18, still lived with them. They worked as twisters in the linen mill.

Soon after, Cordelia and Henry moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, along with daughter Isadora. He received an increase in his pension, to $24 a month, in 1912, and to $35 in 1919. Henry died later that year, aged 87, of nephritis. The government paid $153 for his funeral and interment in Elmwood. Unfortunately his death date was not added to his tombstone.

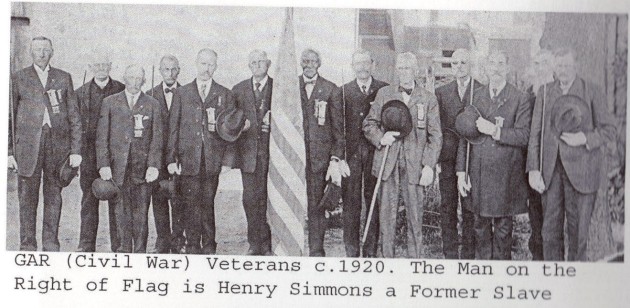

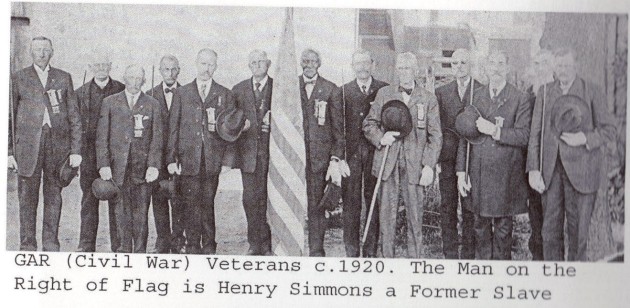

It would be interesting to know for sure how Henry found Schaghticoke. He evidently fit into the community, though it was as rare for a black family to live in the village then as it is now. He lived surrounded by women- his daughters and granddaughters. He was a member of the local post of the G.A.R. The testimony of his neighbors in the pension file clearly shows that he was a valued member of the community who suffered almost daily from his war service. He must have had an amazing constitution!

This photo appeared in two local books: Arthur Herrick’s “Stand Proud Sonny” and Richard Lohnes’ “Schaghticoke Centennial Booklet”. This is Herrick’s caption, wrong on two counts- Henry was not a slave and the photo was before 1920. Lohnes says this is the Hartshorn G.A.R. Post (the Schaghticoke one) c. 1915.

So you are asking, where is the fiction? Arthur Herrick, born in 1903, grew up in Schaghticoke. When he retired from his printing business in Mechanicville in 1967 he wrote his memoirs, published as “Stand Proud Sonny: Village Life at the Turn of the Century,” edited by Walter Auclair. There is a long passage in the book where Henry recounts his life story to the author, then a child. As far as I can tell,the story is entirely false. Was it made up by Arthur or Henry? I’m assuming that an old man had a great time telling all of this to a gullible child. As recounted, Henry was an escaped slave from Virginia, educated alongside the son of a beloved master. After his death, Henry was employed as a stud, fathering 300-500 children! As the war began he escaped, joining the cavalry, staying in the Army long after the war, serving all over the West and ending up in Vermont, where he met his wife and retired from the Army on a partial pension. All of this is false, including his final statement that there was a place reserved for him in the Soldiers’ Plot at Elmwood – his family has its own plot.

Central stone in the Simmons plot at Elmwood. Henry has his own small stone as well.

To me, while Henry’s true story is not as exciting and salacious, it is commendable. He was a hard-working family man who found a niche and lots of support in a conservative upstate community.