It’s time to return to one of the signature industries of Schaghticoke, black powder manufacturing. As I have already written, the Schaghticoke Powder Mill was begun in order to produce powder for the U.S. military in the War of 1812. Josiah, James, and Nicholas Masters, sons of James Masters, who had brought his family to Schaghticoke from Fairfield, Connecticut about 1781, founded the mill. Josiah had been a U.S. Congressman just before the war, and certainly his political connections had something to do with its founding. The mill was located on the north bank of the Tomhannock Creek, just west of where it crosses Route 40. If you wish to read more about the Masters and the founding of the mill, I suggest you check out my earlier post about the Masters.

As I begin what will be a very long post, I want to say that I have worked on this opus for a very long time. I began my research with Peril in the Powder Mills: Gunpowder and its Men by Anne Kelly Lane and David McMahon, which gives basic history of the mills. They did lots of great research. I have found out more about the men who led the powder mill throughout its history.

So beginning with the founders of the mill, though I think that all three Masters brothers, Josiah, James, and Nicholas, were involved in the mill, upon Josiah’s sudden death in 1822, the mill was sold to Nicholas for $1059 + $159 interest. So Josiah had owned the mill in deed. James died in 1828. Nicholas was 77. The mill remained solely in the control of the Masters family until 1836. Nicholas died in 1838, so hung on almost until his death.

At the point of Josiah Masters’ death in 1822, the mill was not growing. Josiah reported in the U.S. 1820 census of manufactures that “When we were at war with Britain (1812-1815) gunpowder could not be imported and so a profit was to be made. At present, owing to the introduction of foreign gunpowder into our country, my business has decreased by more than half. This can only be remedied by a heavy duty on foreign powder which takes the preference in market not because it is superior in quality but because of the predilection of the American people in favor of foreign manufactures.” (Kloppott ) The Masters owned considerable farm lands, so at least they had other sources of income.

Nicholas Merritt, son of Nicholas, carried on in the family business. Presumably he had the interest to do so over his brother and male cousins. Nicholas, Sr. and his wife Sally Phelps had had two sons. Albert Phelps, who was born in 1782 in Schaghticoke, lived in Vermont for the middle part of his life, returned to town by 1840, and died as a farmer in Schaghticoke in 1854. Nicholas Merritt, born in 1790, became the powder maker. Turning to the other original partners, James had a daughter, Fanny, who married Munson Smith, a local miller and entrepreneur, and five sons, but four died young, and the other, Robert, was a farmer in Galway, Saratoga County. Josiah, the former owner of the company, also had a number of children, but they all left town. Josiah’s first wife died young, and their children were sent away to school. His second wife moved away after his death with their children, who were very young when their father died. So Nicholas M., son of Nicholas and grandson of James, was left as the one who carried on in the family business.

Nicholas Merrit Masters graduated from Union College in Schenectady in 1812, according to their catalog of graduates. His son John’s obituary indicated that he graduated from Williams College, but I did not find that to be true. He was educated as a lawyer. He married Ann F. Thomas (b. 1796) of Sandy Hill in Washington County in 1815. They had three children, two daughters who died young, and son John T., who was born in Troy in 1819. John graduated from Union College in 1831.

Besides operating the powder mill, Nicholas was a lawyer, surrogate judge of the county from 1818-1820, justice of the peace in Schaghticoke from 1828-1829, a New York State assemblyman at least twice, supervisor of the town of Schaghticoke in 1841-1842, and in general very involved in politics. After his term as surrogate, Nicholas was always referred to as Judge Masters. While surrogate, Nicholas was nominated as a Republican candidate for State Assembly. He also sat on the central committee of the county party.

As I said, Nicholas served as a NYS assemblyman at least twice, in 1832, as a Republican, and in 1855, as a Democrat or a “Soft Know-Nothing.” He was a Democratic Presidential elector in the 1844 election of James K. Polk. At a Republican gathering in Troy in 1855, a letter from “the venerable” Nicholas was read aloud, and “received with rounds of applause…every sentence of his letter was loudly cheered.” He was a delegate to the State Republican convention in 1858. I am not going to try to explain all the changes in those political parties in the 19th century, but suffice it to say that the parties were very different than they are today, and went through many, many changes of names and philosophies.

I have found that prominent men in the 19th century were involved in many activities. This was true of Nicholas M. Besides working as a lawyer, judge, and politician, he was a trustee of the Presbyterian Church in Schaghticoke for many years. He was one of three commissioners of the Pittstown Bridge Company, established as a corporation by the NYS Legislature in 1825. In 1848, he and others applied to the county board of supervisors to rebuild that toll bridge, so he remained involved for many years. He held the mortgage on former judge and Congressman Herman Knickerbacker’s property, foreclosed upon his death in 1855. Herman owned water rights on the Tomhannock Creek affecting the powder mill, so this investment may have been both a friendly and a strategic one. Nicholas, his son, and several other powder mill executives even bought property in Brooklyn in the 1850’s. Nicholas had his fingers in many local and statewide pies.

Let’s look at Nicholas M. in the census. In 1850, the first census to give much information, Nicholas was 60, with real estate worth $10,000. His occupation was still manufacturer, though there were a number of younger men in charge at the powder mill by this date. I believe that he lived in the house now occupied by Linda and Andy Bunk, just south of the bridge over the Hoosic River on Route 40. By 1855 he had real estate worth just $3000, and was listed as a farmer. He and wife Ann lived with just one servant. He had moved, as the 1856 map of the town shows his farm on the east side of today’s Akin Road, to the north of Masters Street. By 1860 he was listed as a “gentleman”, with real estate worth $3500, and a personal estate of $1000. By 1870 he had moved to live with his son John T. in Greenwich. He died in 1872. The railroad put on a special train to take mourners from Johnsonville to Greenwich for the funeral. He is not buried in the family cemetery or in Elmwood.

Before being the rectory, this was the home of at least two powder makers: Riley Loomis and John T. Masters

John T. Masters started on the track to take over from his father at the powder mill, but got derailed by politics and an advantageous marriage. John went to Union College with Chester A. Arthur, the future President, and formed a friendship that was maintained for life. In 1839 he married the daughter of Mr. Mowry, who owned a metal tea tray factory in Greenwich, and moved there, going into business with his father-in-law. He did list “gun powder manufacturer” as his occupation in the 1855 census. The next year, he sold his house in Schaghticoke, later the rectory of St. John’s Catholic Church. I think he left the mill at that point. Prominent in Republican politics, he was appointed the Internal Revenue Collector for the Washington and Rensselaer County District just before the Civil War, then his friend Arthur brought him into the Adjutant’s office with him during the war. He continued to work for the Department of War, keeping his position even after the death of his patron Arthur in 1888. He died in 1894.

As the Masters left, other men joined the management of the powder mill as the 19th century progressed. All were immigrants to town from New England. The first was Wyatt R. Swift. According to “Landmarks of Rensselaer County” by George Anderson, Wyatt was born in Monmouth, Maine in 1798. After receiving a “good education” Wyatt was “sent” to Schaghticoke to superintend the Joy Linen Mills. Benjamin Joy of Boston built the mill, with his brother Charles as his local agent. The 1855 census reports that Wyatt had been here for 28 years, which would put his arrival at 1827. He does not show up in either the 1830 or 1840 census, though he was certainly here. After Benjamin Joy died in 1829, Wyatt left the mill and “purchased a controlling interest in the Schaghticoke Powder Mills and became its general manager,” again according to Anderson. I think this is a little off in date. Wyatt was still running the Joy Mill in 1831, when Richard Hart conducted a local mill census. According to McMahon and Lane in “Peril in the Powder Mills”, Wyatt joined the powder mill in 1836, and the company was then called Masters and Swift.

Like other prominent men of his era, Wyatt was involved in many aspects of the life of his new community. Right from the start, he was master of the Homer Masonic Lodge, serving from 1828-1834. He also attended state masonic conventions. In 1831 he was a stockholder of the canal bank. He was also involved in politics, acting as delegate to many Rensselaer County Whig Conventions, serving as Supervisor of the town in 1859, and running again in 1860 though he was defeated. At the same time he was a director of the Troy and Boston Railroad and of the Commercial Bank, along with many prominent Trojans.

Also early in his life in our community, Wyatt was extremely active in the Temperance movement. He was the President of the Schaghticoke Temperance Society in 1832 and 1833, and attended State Conventions on its behalf. The local society had 530 members, an astonishing total in a small community. In 1832 he reported “we have much to encourage us to persevere in the cause of temperance; we have had three public meetings at which addresses were made on the subject.”

Like all of the other officers and owners of the powder mill, Wyatt was a member of the Presbyterian Church. He joined in 1839, though he had certainly attended before that. At the same time he became a trustee of the church, a position he held until his death, and also served as chorister- director of the choir, and superintendent of the Sunday school. In 1846 he was a member of the building committee, charged with constructing a new church on the same site as the old.

I think that Wyatt married at the relatively advanced age of 52, in 1850, to Maria O. Morris, age 25, daughter of Jedediah and Olive Morris of Connecticut. The article about him in Anderson’s “Landmarks of Rensselaer County” gives that date. He states that she and her parents came here from Connecticut about 1824. Indeed Jedediah does appear in the 1830 and 1840 census. His wife Olive was baptized in the Presbyterian Church in 1826 and Jedediah a couple of years later. The record adds that he died in 1841. The 1850 census captures the new family: Wyatt a manufacturer with real estate worth $4000, wife Maria, and her mother Olive Morris, aged 52, plus two Irish servants, one male, one female. The Swifts lived next door to William Bliss, a bookkeeper in the mill, and his wife Ann, both just south of the Catholic Church on Route 40, across the street and south of the home of Nicholas Masters.

An article in the Troy “Daily Whig” in March 1844 records the next change in the powder mill ownership. The Schaghticoke and Tomhannock Powder Mills, known as “Masters, Swift, and Company”, was now to be called Loomis, Swift, and Masters. The Loomis was Riley Loomis, whom I will discuss later. The Masters involved were Nicholas M. and his son John T. They will “Hereafter keep at their works a constant supply of blasting, sporting, and rife powder in kegs and canisters, which they will sell on reasonable terms.”

A big question as far as I’m concerned is just when the powder mills moved from the Tomhannock Creek, west of where it crosses Route 40, to the Hoosic River. I was always told that the move was in 1849, but I have found no primary source that mentions that at all. The “Powder Mill Farm”, located where the powder mill came to be on the Hoosic, south of Valley Falls and north of what is now the Brock farm- then the Myer farm- was purchased before 1835. The 1856 map of the town shows operations in both locations. Clearly by the Civil War, all powder operations were on the Hoosic, while the keg shop remained on the Tomhannock. A letter written by E.L. Prickett, a 20th century superintendent of the factory, indicates that the company had “ a complete powder plant, a saltpeter refinery, the keg factory, and charcoal kilns,” to make the charcoal needed in the manufacturing process, and that it only produced about 200 pounds of powder per day in 1836. Evidently information on the location of the mills was so well known as not to need comment.

From the 1856 map of the Town of Schaghticoke- powder mill and keg factory on the Tomhannock Creek

One of the constant themes of powder making is the explosions which were inevitable in the process. The buildings of the mill were always very small and located quite far apart from each other. Charcoal needed in the process was made at a distance. The idea was that the inevitable explosions would be as small as possible, and that one explosion wouldn’t go on to cause another. “Peril in the Powder Mills” has a page-long list of fatalities in explosions over the years. An article in the Troy “Times” in 1929 quoted editor of the Schaghticoke “Sun” on his “complete” list of explosions. I have found a few others reported in newspapers all over the country over the years.

Charcoal making

Most of the explosions occurred in one of the wheel mills, where the ingredients of black powder, charcoal, sulfur, and potassium nitrate, were mixed together and there was the greatest chance of sparks from friction. Wheel mills weighed up to eight tons and rotated in large cast iron pans with the addition of some water. This could be a very volatile process. Then the powder went to the press house, where it was squeezed into one-inch thick cakes. The powder was extremely flammable in this state. It then went to the corning mill, where the hard cakes were ground to smaller pieces. This was occasionally a site of trouble as well. The powder was sorted by sifting through screens, glazed with graphite, and packed into kegs or cans. There was a need for extreme care all along the way. One explosion at Schaghticoke was of powder stored in a railroad car.

Wheel mill

The earliest report of an explosion at the mill that I have found was in March, 1840, when the St. Lawrence “Republican” stated, “ About 3 o’clock on Monday morning last, the powder mill of Messrs. Masters and Swift of Schaghticoke blew up. No lives were lost. It contained about 60 kegs of powder.”

The November 28, 1848 Oneida “Morning Herald” reported, “The cylinder mill of the Tomhannock Powder Works, owned by Messrs Loomis, Swift, and Masters, of Schaghticoke, exploded, says the Troy Budget, on Thursday morning last at about 4 o’clock. The building contained 64 kegs of powder in an unfinished state. Loss from $1000 to $1500. The building was blown to atoms. Fortunately no lives were lost.” This indicates that the mill was still on the Tomhannock. I would assume that the cylinder mill was another term for the wheel mill.

Reproduction casks of powder at Fort Stanwix

The first explosion listed in “Peril in the Powder Mills” was in 1849, when John Kewley and John Gallagher died. I cannot find any mention of this explosion in the newspapers of the time. I wish I could as this might have indicated where the mill was. I know that John Gallagher left a family: wife Roseann, 34, born in Ireland, plus five children aged 10 to 3, all born in New York. And John Kewley left wife Jane Kane Kewley, born on the Isle of Man, aged 35, plus five children aged 14 to 2 and his mother-in-law, Margaret Kane. He had been in town since at least 1840, according to the census. His family stayed in town. Margaret Kane died in 1879 and Jane Kewley in 1900. John and both women are buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

The Powder Company had grown tremendously since the 1830’s. When the Crimean War began in 1854, Great Britain and its opponent, Russia, both turned to the U.S. to supply gunpowder. Hazard in Connecticut, DuPont in Delaware, and Schaghticoke were all sources of powder. The 1855 NYS census captures the volume made here. The real estate at Loomis, Swift, and Masters was worth $22,000, the tools $2000. In 1854 they had used 700,000 (or 70,000- unclear writing) pounds of saltpeter, worth $49,000; 95,000 pounds of brimstone (sulfur), worth $2850; and 400 cords of wood, worth $1800, to produce 38,000 kegs of blasting powder worth $76,000. The mill operated by water powder and employed 15 men, paid $33 per month. This was a high wage, based on the danger of the work. A separate operation, definitely on the Tomhannock, made the kegs. It had $3500 worth of real estate and $1000 worth of tools. 200,000 feet of lumber worth $2500 and 456,000 hoops worth $1375 very naturally made 38,000 kegs, worth $6,500. The mill was also powered by water and employed six men who made $24 per month.

In the midst of the war production, on November 17, 1855, there was another explosion. The Troy paper reported that “The principal grinding mill was greatly damaged by the explosion, which was supposed to have been caused by friction. One of the employees was fatally injured, having been struck upon the head by a large piece of stone.” According to “Peril in the Powder Mills,” two men died: Benjamin Neal and Edward Delaney. I haven’t found either of them in the census. The diary of William and Frank May records that Delaney and a man named Peter Cook or Coon died in an explosion on May 7, 1859, and that a man named John Burdick died in another explosion in October 1859. These details vary with the source, so I guess the message is that there were frequent explosions with one or two fatalities.

In 1856 there was another change in ownership of the powder mill. Riley Loomis and “Masters” left the masthead, and the new firm was Swift, Bliss, Greeley, and Company. I will discuss Bliss and Greeley later. John T. Masters, son of Nicholas M., was still involved in the company, though he sold his house in Schaghticoke that same year, and had married a girl in Greenwich. I would say that his absence from the title of the company indicated that his involvement in the mill was decreasing.

The Schaghticoke Powder Company was incorporated in 1858, with Wyatt Swift as its President. This meant that it was now owned in stock shares. I think these shares were closely held, by just the officers of the company. By the 1860 census Wyatt’s occupation was just listed as “gunpowder”, and he had $19,000 in real estate, with a personal estate of $600. He and his wife had adopted Jeanette P. Russell, then age 11, a girl from Hoosick Falls. Still next door was William Bliss, now listed as a gunpowder manufacturer, with another owner of the company, Paul Greeley, just a few doors away.

A newspaper article in the Burlington “Free Press” on August 19, 1859, speculated about the cause of a big explosion the day before as being a powder mill blowing up, before concluding it was a meteor strike. In the speculation it reported “fourteen wagons loaded with powder had started from Schaghticoke that morning.” This gives us a glimpse both of quantity and transportation, as the powder could have gone by train. Wagons were safer. It must have been quite a procession.

With the start of the Civil War, business was booming (no pun intended) at the powder mill. I have written before that it was the 4th largest supplier of powder for the Union, and about the terrible explosion at the mill in 1864 when four workers died. The plant produced 3600 pounds of powder per day. The company used about 600,000 pounds of saltpeter and brimstone to make $206,000 worth of powder in 1865.

President Wyatt R. Swift must have been busier than ever with the demands of war production. In addition to his church, political, and other business involvement- in banks and railroads- he was elected County Superintendent of the Poor in 1860. He would have been familiar with the job as he had been a member of the County Board of Supervisors in his role as Schaghticoke Town Supervisor. Wyatt died March 12, 1863. This must have left a big void in the company. I have not found out why he died, but it must have been unexpected as he was so active.

In his will, Wyatt left $5000 in trust for his adopted daughter, to his wife the house, furniture, horses, carriages and sleighs, plus $10,000, which she could take in stock of the Schaghticoke Powder Company at $1000 per share. If his wife died before his mother-in-law, the latter would get the use of his house, best horse, carriage, and furniture plus $600 per year. He also left bequests to a few nieces and nephews, and money to care for his mentally ill and institutionalized sister Harriet. His partners Paul Greeley and William P. Bliss were executors, along with his wife. Final disposition of the will did not occur until 1900. The Troy “Times” reported that Wyatt’s funeral was April 3, 1863 at the Presbyterian Church, attended “by a large number of townspeople, though few were present from Troy.” The Swift plot was one of the first in the new Elmwood Cemetery in Schaghticoke.

I’d like to return to 1844, and the renaming of the powder company from Masters and Swift to Loomis, Swift, and Masters. While Nicholas and John Masters had gotten into the mill by inheritance, and Wyatt Swift transitioned from textiles to powder, Riley Loomis was an experienced powder maker who apparently bought into the mill just before retiring.

Riley Loomis was born about 1790 in Southwick, Massachusetts, one of twelve children of Ham and Elizabeth Loomis. He married Roxana Atwater of West Springfield in 1815. The couple had a daughter, Roxana Marie, born in 1817, and a son, Riley Atwater, born in 1818. Though the son lived until 1854, I have not been able to find out anything more about him. Around 1820, Riley Sr. and the brothers Winthrop and Walter Laflin moved to Lee, Massachusetts and began manufacturing powder as Laflin, Loomis, and Co. The Centennial History of Lee states that they provided powder for the excavations on the Erie Canal, and soon had to begin a second mill in town, manufacturing 25 kegs (2500 pounds) per day. However, “explosions were frequent, causing fires and death…In September 1824, the mill at the north end of the village exploded. Five tons of powder burned, damaging many houses in the neighborhood and producing consternation throughout the town. Mr. Loomis was near the mill and came near losing his life from the falling timbers.” There was lots of local protest against rebuilding the mill, and it did not rebuild. The History reports that the men converted to making paper bonnets and wire. As papermaking from wood pulp did not really begin until the 1870’s, this would have to be paper made from rags. The 1820 “Berkshire Sun” reported that Laflin and Loomis had white flannel for sale, so perhaps the men also did textile manufacturing as well.

The Lee history does not mention that the Laflin family had been manufacturing gunpowder in the region since just after the Revolution. Matthew Laflin, whose wife was Lucy Loomis, began making gunpowder about 1790. His sons and grandsons continued after him. While the mills at Southwick closed, the Laflins moved their operation to Orange County, New York. Laflin, then Laflin and Rand, became second only to DuPont as a maker of powder in the U.S. Laflin will come back into the story later. The famous Hazard Powder Company in Enfield, Connecticut grew from a company founded by Allen Loomis. I think he was Riley’s brother. One of the early histories states that Laflin bought out a powder operation operated by the Loomis brothers. It seems clear that Riley came from a powder background, though at this point I haven’t been able to figure out all of the details.

Riley Loomis

Whichever the case, Riley moved to Schaghticoke after 1830. The first time I found him in the records was in the July 1, 1834 “Troy Budget,” when he attended a meeting of the Republican Young Men at the house of Colonel B.K. Bryan, along with Isaac T. Grant. Bryan lived on the Tomhannock near the powder mill. Riley was on a committee to draft resolutions. He had served as a representative in the Massachusetts legislature in 1831, so had political experience. Though Riley did not hold town or county office thereafter, he was very involved in politics through town and county committees. For example, the April 1840 “Troy Budget” reports on a meeting of the Democratic Republicans of Schaghticoke to nominate candidates. Riley Loomis was the chairman. The November 6, 1848 edition stated he was a Presidential elector for the Free Soil party, “known through the county as a uniform and consistent democrat and a generous true-hearted man.” Riley’s obituary states that he “started as a Jeffersonian Republican,” staying true to the tenets of the party as its name changed over the years. “He contributed liberally for party purposes, but although often urged to do so, he could never be induced to accept a party nomination for office.” The Loomis’ also joined the Presbyterian Church. In 1836 he was elected a trustee of the church, along with fellow powder maker Nicholas M. Masters. Wyatt Swift served as a trustee about the same time.

Of course Riley had come to Schaghticoke for business. One wonders why he stayed with powder, a much more dangerous business than textiles. I found him in the 1840 census for town, with a family of one male and one female between 50-59- presumably he and his wife, though they were five years younger than that, one male from 20-29, presumably their son Riley, one female from 20-29, presumably their daughter Roxana Maria, one female from 10-14, and two free blacks from 10-23, one male and one female. Two of the household were in manufacturing, father and son. In 1839 Riley bought for $1500 property on the north side of the Tomhannock Creek from Herman Knickerbocker, along with 1/3 of the water from Knickerbocker’s dam. The property description records that the land abutted property Riley was already leasing from George Tibbits, and that this piece was on the highway. Riley was also constructing a dam, and had the privilege of “flowing” onto Knickerbacker’s land- creating a mill pond. Riley also had a right of way from the highway to the mill. The powder mill and its keg shop were just downstream from this, so it sounds like Riley was adding to the mill property. The name change of the powder mill didn’t occur until 1844, so perhaps at this point he was setting himself up as a competitor? His obituary states that he first was in business in his own name, then with Masters and Swift, so perhaps this is an indication of that.

Riley also built a home in Schaghticoke. The January 3, 1851 “Troy Budget” describes a “valuable house and lot” for sale by Edwin Smith, on the south side of the Hoosic, next door to the residence of N.M. Masters, and “erected and formerly occupied by Riley Loomis.” “The location is elevated and healthy and the scenery unusually fine. The buildings…are large and commodious. On the premises are a good fruit and flower garden, extensive pleasure grounds, a well of pure water and two cisterns, in short everything necessary to render it a desirable country residence.” I think this is the former rectory of St. John’s Church, just south of the bridge on route 40.

Ironically, just as Riley became the first name in the Powder Mill partnership in 1844, he moved from Schaghticoke to Troy. His obituary states he moved in 1842, and indeed, the Troy “Budget” of October 5, 1842 lists him as the chair of a meeting of the Democrats of the First District over the Washington Market in Troy. He apparently had moved seamlessly from Schaghticoke to Troy. Troy was a booming city, and perhaps he felt he needed to be part of it, and its society. He maintained his ties with the Schaghticoke Presbyterian Church, however, serving on a committee which studied building a new church in 1845-1846, and only being removed as a trustee in 1850. I think he also kept a home for some time locally.

The Loomis “cottage” on Washington Park in Troy

At first Riley and his family lived at 30 3rd Street in Troy. He joined the Presbyterian Church. In November 1844, daughter Roxana Marie married John Wentworth. The 1850 census records Riley, at age 55, as a manufacturer. Roxana was also 55. Daughter Roxana Marie, here called Mary Wentworth, age 30, and her son John Wentworth, 8 months old, were living with her parents at this point. The household also included three young Irish serving girls and a young Irish laborer. The 1855 NYS census shows just Riley and Roxana in the house, described as brick and valued at $12,000, along with three different Irish girls and a different Irish man, the driver. I am not sure if this was the old house, or the new one described below. The listing of Riley as a manufacturer indicates to me that he continued to run the powder mill.

As I said earlier, the next change in Powder Mill ownership was in 1856, when Loomis and Masters left the title, and the company became Swift, Bliss, Greeley & Co. Certainly this is when Nicholas M. Masters retired. This may reflect Riley’s retirement as well. At that time he built a house on 3rd Street on Washington Park in Troy, described in his obituary as “the unique, spacious, semigothic homestead.” Washington Park, between 2nd and 3rd Streets, is accessible only to those residing on the park. This was one of the most fashionable places in Troy to live. The house was very different from the several- story brownstones being built on the park by the captains of Troy industry. It was a one- and- a- half story cottage with a large yard on either side. It had just four bedrooms, a parlor and dining room, bathroom and kitchen on the main floor. (illustrated)

The 1860 census records Riley Loomis and wife Roxana, both 69, living there, with just one Irish servant girl. His occupation was listed as “gentleman”, further confirmation of his retirement. Riley listed his real estate as worth $125,000 and his personal estate as $100,000. I find this incredible. This is far more in both categories than anyone I can find in Troy that year. The whole powder mill property was valued at $22,000 in 1855, and Riley’s house sold for $32,000 ten years later. I can’t account for it. The 1865 NYS census lists the couple living alone, with Riley as retired. He died the following year.

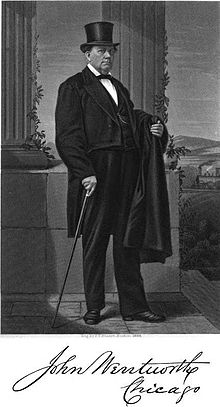

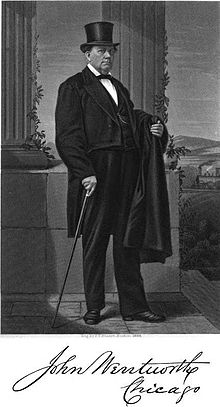

Long John Wentworth, Mayor of Chicago, husband of R. Marie Loomis

Returning to the daughter, Roxana Marie, or R. Marie, as she was most often referred to, married a wealthy Chicagoan. John Wentworth, known as “Long John,” was born in New Hampshire in 1815 and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1836. He was first a newspaperman in Chicago, but got into politics. At the time he married Marie, November 13, 1844, he was in his first term as a U.S. Congressman. I don’t know why John stopped in Troy or how he met Roxana Marie. If the Loomis’ had moved to Troy to get their daughter out into a wider society, they achieved their goal. The marriage was reported in both the local and New York City newspapers. I assume that she was living with her parents at the time of the 1850 census as she did not want to live in Washington, D.C., was in the middle of having babies, and knew no one in Chicago. John served until 1855 in Congress, then again in 1865-1867. In between, from 1857-1858 and 1860-1861, he was Mayor of Chicago. Meanwhile he amassed a fortune. The 1860 census for Chicago listed his real estate as worth $300,000, and his personal estate as $30,000. It lists his family as “Mrs. Wentworth, 21, and Rosinda, 5.” This must have been R. Marie, really 43, and daughter Roxana, who was 5 or 6.

In their personal lives, the Wentworths and Loomis’ suffered many tragedies. On July 14, 1846, while on a visit to his paternal grandparents in New Hampshire with his mother, Riley Loomis Wentworth, their only child, died of croup at age 10 months. He had been born at his maternal grandparents’ home in Schaghticoke. Another child, Marie, was also born at her grandparents’ home in 1847, and died there of cholera on August 29, 1849. And a third child, John, born in Troy in November 1849, died there of lung fever on February 23, 1852, while his parents were in Chicago. And Riley Atwater, the only son of Riley and Roxana Loomis, died in Schaghticoke in September 1854 at the age of 35. The fourth Wentworth child, Roxanna Atwater, was born in Troy on October 28, 1854. This was surely a happy note coming so soon after her uncle’s death. But the fifth child, John Paul, born in Troy on October 18, 1857, died there on March 27, 1858 of congestion of the brain. A biography of John Wentworth, “Chicago Giant,” states that Marie “was always a shadowy figure in (Wentworth’s) life, and her demonstrable influence upon his career was so slight that one easily forgets he ever deserted bachelorhood.” I wonder if Marie was tied down through much of her marriage by her five pregnancies and ill children, and preferred to have the support of her mother and father in Troy.

When Riley died in 1866, his obituary in the Troy newspaper said “his health had been failing for years and his death was not unanticipated.” Unfortunately for us, it does not include many details of his connection with the Powder Mill. Of course, Mrs. Loomis inherited from her husband, but the city directory reveals that she moved to 102 3rd Street. Daughter Marie Wentworth died in February 1870 and Roxana Loomis the following month. Riley and Roxana Loomis, Roxana Marie Wentworth and her four children who died young are all buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

The elegant home on the park in Troy, which had already been passed to the Wentworths, was sold that same year at auction for $31,250 to Reverend A.T. Chapman. The inventory of Roxana’s estate is relatively modest, but does include a diamond jewelry worth about $1500, plus quite a lot of silver plated ware. Roxana had just seven dresses, but also a Russian sable coat and muff worth $1000. There was some pricey black walnut and mahogany furniture in parlor and bedrooms. At the auction of the property, an elegant “Clarence”, a type of carriage, made new for $2500, sold for $725, and a barouche sleigh for $180. Granddaughter Roxana Wentworth and her father John Wentworth were the only remaining heirs. The Loomis home was torn down in 1916, and is now the site of apartments made from St. Mary’s School.

As I said above, with the retirement of Riley Loomis in 1856, the Powder Company’s formal name became Swift, Bliss, and Greeley. I have talked of Wyatt Swift, who died in 1863, now on to Greeley. Paul Greeley was born in 1814 in Salisbury, New Hampshire, the son of farmer/tanner Moses Greeley and his wife Hannah Eaton. He was about five years younger than Wyatt Swift, seven than Bliss.

According to the Greeley genealogy, Paul went to Savannah, Georgia in 1836 and worked as a bookkeeper there until 1843, when he went to Hazard Powder Company in Connecticut as a bookkeeper and “general assistant.” Hazard had been founded in Enfield, Connecticut by Colonel Augustus Hazard in 1835. Paul married Caroline Woodworth of New York City in Albany the next year. She, the daughter of Martin and Abigail Woodworth, was just 19. One wonders how they met and why they married in Albany. They had a son who died at birth in 1846. A daughter Emily died at age seven months in 1848, but a second Emily was born in 1854. The 1850 US census found them in Enfield, Connecticut. Paul was listed as a 35-year-old manufacturer of powder. Wife Caroline was 23. According to “Peril in the Powder Mills,” Paul started another company, Enfield Powder, in 1849, with several other investors. This company was taken over by Hazard in 1854, perhaps leading to the Greeley’s move to Schaghticoke. The Greeley genealogy states that he was the Superintendent of the American Powder Company in South Acton, Massachusetts at that time. Whichever it was, Paul was able to amass some capital.

Paul became one of the owners of the Powder Mill when the Greeleys moved here in 1856. He would have been a mature man of 42. That year Caroline joined the Presbyterian Church. The following year son Edward Allen died at age six and a half. Paul joined the church in August 1858, when he was immediately elected a trustee of the church, joining his fellow powder makers. Their final child, Emma, was born that year.

Paul and Caroline lived near partners Wyatt Smith and William Bliss in his new town, on the current route 40 just south of where the bridge crosses the Hoosic River. The 1860 US census captured the family at its largest: Paul, 46, a gunpowder manufacturer with a personal estate of $15,300; Caroline, 35; Ellen, 6; and Emma, 2; plus mother-in-law Abigail Woodworth, age 70; and a 25- year-old Irish domestic servant, Bridget. Paul must have been instrumental to the operations of the mill during the great demand of the Civil War years, especially with the death of Wyatt Swift mid-war. The family seemed to have been warmly welcomed into the community.

Unfortunately Paul’s tenure at the powder mill had a very tragic end. The Troy “Times” reported his death on May 22, 1866. Paul, John T. Masters, the last of that name associated with the company, and several others had gone to Pennsylvania on business. They arrived at a station near Hazelton, Pa., where they had to change trains. For reasons unknown, Paul “stepped from the platform (onto) the track,” into the path of an oncoming train. “He hesitated for an instant, considering on which side of the track he should jump in order to escape,” but was hit by the tender, “which was in advance of the locomotive.” It knocked him down, leaving his legs on the track to be run over by the train. “He was immediately picked up, still conscious as ever and not even fainting.” His companions put him in a train car and took him back to Hazelton. Looking at his mangled feet, he said, “I am ruined. But is it possible this is death? It may be. If so, am I prepared? I think I am.” The next day both legs were amputated below the knee. He died several days later, before his family was able to reach him.

According to the paper, the village of Schaghticoke was in shock. “Mr. Greeley was no ordinary man. He possessed a benevolent heart; he delighted in doing good. He had the means, the will, and the executive talent to accomplish his purposed and those purposes were always beneficent.” Paul was doing a great job as a principal owner of the mill and had just been ordained a deacon of the Presbyterian Church, where he was also chairman of the board of trustees. Would the Schaghticoke Powder Company have been taken over by Laflin in 1871 if Greeley had survived? Impossible to know.

Greeley Plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Schaghticoke

Greeley Plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Schaghticoke

Paul was buried in the Greeley plot at the brand new Elmwood Cemetery, where there are also tombstones for his children who had died young. He was the neighbor of co-owner Wyatt Swift even in death. Widow Caroline Greeley was still in Schaghticoke in 1870. She had an estate of $8000. The family included daughters Ellen and Emily plus one domestic servant. Ellen married a man named Charles Durfee a couple of years later and by 1880 had moved to Geneseo. They already had three sons. Mother Caroline and sister Emma lived with them. By the 1900 census, they had all moved to Oberlin, Ohio. Ellen was a widow, who had had five children, four living. Emma had been married for fifteen years and had two sons, though the census does not list her husband in the family. Caroline lived with her daughters and grandsons until she died in 1902. She is buried beside Paul in Elmwood Cemetery.

Just after Nicholas Masters and Riley Loomis got out of the Powder Mill, in 1858, William P. Bliss became Secretary, and was listed in the company name. It’s time to look closer at this man. William Porter Bliss was born in 1807 in Stockbridge or Lee, Massachusetts, son of Joshua and Grace Porter Bliss. Joshua was a carpenter. William married Ann Jane Goodrich in 1833 in Sheffield, Massachusetts. I have not been able to learn anything about the early training of William. He lived in the same area of Massachusetts as Riley Loomis, and it is tempting to think he worked for him and followed him to town, but I just don’t know.

The Bliss’ moved to Schaghticoke in 1837. In August of that year, Ann joined the Presbyterian Church, followed by William in May 1838. In July 1839 William was elected a trustee of the church for the first time. He was involved in the church for the rest of his life. In 1854 he was a member of the United Church Board for World Ministries, and in 1858 a member of the Board of American Commissioner for Foreign Missions, carrying his religious commitment to a national level. He was chorister at Schaghticoke Presybterian from 1837-1874, leading the choir for an amazing 37 years.

The 1840 census for Schaghticoke listed William and Ann, plus one male and one female aged 15-19. William was reported as working in manufacturing. A Bliss genealogy states that William and Ann had no children, so I’m not sure who the teenagers were. I also can not be sure that he worked at the Powder Mill. The 1865 census reports that at some point Ann had had one child, which evidently did not survive. By the 1850 census, the first to list names, William, 42, was listed as a bookkeeper, with a personal worth of $3000. Wife Ann was 35, and an 18-year-old name Allace L. Bacon, lived with the couple. She was also born in Massachusetts. The Bliss’ are listed next door to fellow-powder maker W.R. Swift, living just south of the Catholic Church on the same side of the street. Riley Loomis and N.M. Masters lived almost across the street. Again, I’m not sure that William worked at the Powder Mill, but I’m betting he did. The powder makers stuck together in residence and worship, as well as business.

Unlike the other powder makers, William was not involved in county and national politics and county committees. He did serve as a trustee of the village of Schaghticoke in the first years after its incorporation in 1867, but not beyond that. He also dabbled in real estate. He and the other powder men had bought a parcel in Brooklyn which was foreclosed upon in 1853. He also bought lot 9 in the village, on the west side of Main Street, near the current VFW. But this was foreclosed upon and sold at auction in 1854. At the time of his death, he also had a perpetual lease on lot 3 in the village.

It seems that William focused on the Powder Mill more than Masters, Swift, or Loomis. His promotion within the powder company is revealed in the 1855 census, when he is listed as a powder manufacturer, now worth $4000. He and Ann lived alone. By the 1860 census, William, now 52, had real estate worth $12,300 and a personal estate worth $3000. He and Ann, now 49, had a domestic servant, Eliza Dobson, a 20-year old Irish girl. Anderson’s History of Rensselaer County states that William was elected President of the powder company in 1868. As former President Wyatt Swift died in 1863, I don’t know who served in the interim. Perhaps the election was a mere formality. I will return to William later.

There is much more to say about the Powder Mill, but I will return to its history later. The following bibliography is for the whole series- already written.

Albany”Argus”, March 1819, 1863

Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1858

Anderson, George, “Landmarks of Rensselaer County.”

Berkshire “Journal”, 1831

Berkshire “Sun”, 1820

Burlington “Free Press”, Aug 19, 1859

Fehrenbacher, Don E., “Chicago Giant”, 1957

Find-a-Grave.com, Chauncey Olds

Greeley, George Hiram; “Genealogy of the Greely-Greeley Family”, 1903, Boston, Ma.

Klopott, Beth, “History of Schaghticoke.”

McMahon, David, and Ann Kelly Lane, “Peril in the Powder Mills.”Infinity, 2004.

“Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church,” 1852

Munsell, Joel, “Catalog of Graduates of Union College”, 1868

NYS Assembly, “Report of Stockholders in NYS Banks” 1831, 1832

NYS Society for the Promotion of Temperance, 3rd and 4th annual reports, 1832 and 1833

Ogdensburg “Journal,” Jan. 17, 1877.

Olds, Edson, “Olds Family in England and America”, 1915.

Oneida “Morning Herald” Nov 28, 1848

Pittsfield “Sun”, 1854, 1870

“Proceedings of the Grand Chapter of Freemasons in NYS” 1829

Rensselaer County deeds, book 48 p 327

Rochester “Republican” Nov 23, 1844

Schaghticoke Presybterian Church records, in historian’s office

St Lawrence County “Republican”, March 1840.

Syracuse “Evening Chronicle” Oct 18, 1855, Nov 20, 1854

Sylvester, Nathan, “History of Rensselaer County”, 1880

Troy “Budget”: Sept 1840, Oct 7, 1843, Oct 27, 1846, Nov 4, 1844, Sept 27, 1847, Sept 24, 1858, June 1847, July 17, 1853

Troy “Daily Times” Sept 27, 1845, Mar 28, 1872, Oct 1855, Nov 15, 1859, Mar 9, 1860, Oct 11, 1854, Apr 4, 1863, July 27, 1861, Oct 17, 1888, May 23, 1866, May 1893, Sept 29, 1892, Feb 3, 1896, Jan 20, 1877, Oct 16, 1889

Troy “Daily Whig” March 11, 1861, Mar 12, 1844, Feb 1837, Apr 12, 1849, Mar 6, 1860, Nov 12, 1860, Jan 24, 1856, Nov 17, 1855, Sept 1, 1874

Utica “Gazette” Nov 12, 1854

Utica “Morning Herald” Oct 24, 1879

Valente, AJ, “Rag Paper Manufacture in the US, 1891-1900”, 2010

Washington County “Post”, Jan 19, 1894, Oct 4, 1892

Wentworth, John, “Wentworth Genealogy”, A. Mudge, 1870.

Will of Wyatt Swift, Rensselaer county book 64, p 36

Greeley Plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Schaghticoke

Greeley Plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Schaghticoke