I have been blogging about the history of Schaghticoke since July 2011, mostly chronologically, and ,with some detours, have reached about 1840. At that point, we can see elements of our modern town, together with holdovers from its colonial past. The town had a population of 3,400, not that different from now, as the town was smaller physically. The southern border of the town was the Deep Kill, which crosses route 40 at Grant’s Hollow. The population skewed young, with 1315 people under 21 and only 129 over 60. 2% of the population, or 76 people were free blacks. 28 of them lived in fifteen families, with the rest living one or two apiece as servants in various white families. I will write about the black families later.

The town government of 1840 was similar in some ways to that of today, with a supervisor, town clerk, and town justices. But there were no town councilmen. There were a couple of election inspectors, four assessors, and a commissioner of highways, similar to today, but there were 32 highway overseers, as men were in charge of maintenance of the road abutting their land. The town also had a couple of poundmasters, as one of the problems in town was animals getting loose and harming crops. Early town laws mandated when cattle could be “free commoners,” in other words, run free. In 1842, the law read that hogs could never be free commoners, but cattle were from May 15 to October 15. The town also had its own sealer of weights and measures and overseer of the poor, both functions done by state and county governments now. There was only one town meeting per year, versus monthly meetings and other special meetings now.

The town also had its own police force, the officers called “constables.” These men were ordinary citizens appointed to fill the positions yearly. In 1844 there were five constables. Town records through the 1840’s show various citizens applying to make new roads. The same thing happens now with a new development, but just less frequently. There already was a lot of the road system that exists now, though the roads were dirt or plank, the main road, route 40, a toll road. The bridges over the Hoosic River, at Valley Falls and Schaghticoke, and the Hudson, at Stillwater, were privately-owned toll bridges. There was a ferry across the river at Hemstreet Park. People traveled by horse, horse and wagon, and on foot for private transportation. Public transportation was by steamboat or canal boat on the rivers and canals, by stagecoach from town to town. Railroads had begun to be built, but hadn’t reached our town yet.

current photo of the Melrose School on Mineral Springs Road

The town was divided into fifteen school districts, each with a one-room schoolhouse, with a total of 840 students. Unlike today, the town oversaw the schools, providing part of the funding, but each district had a local school superintendent. There was no public education beyond about 8th grade available in town. A few children of wealthier families were sent to private schools in Troy, Greenwich, Fort Edward, and elsewhere, and fewer went on to college. The census states that only six people were illiterate. I wonder what the definition of illiterate was. I feel that number is definitely less than the reality, just from the wills and documents of the period I have read where people were unable to sign their names, using just an X.

Grain cradle of the kind patented by Isaac Grant and Daniel Viall

As today, there was just one village, then called Schaghticoke Point, grown up around the bustling mills in the gorge of the Hoosic River. There was a small settlement in Grant’s Hollow, where Isaac Grant had an agricultural machinery factory and store. It had a school house, church, and post office. There was another settlement at Schaghticoke Hill, on route 40 just south of where the Tomhannock Creek crosses. It grew up because of the grist, textile, gun powder, and keg mills on the stream, and had a school, church, blacksmith shop, and at least one small store. Where we might have auto repair shops, there were blacksmiths, who shoed horses and repaired wagons and other items made of iron. There were a number of inns, some more like bars, others more like hotels. Sometimes a home would have one room that would be a general store or a tavern. Residents of Schaghticoke had some choice of churches in 1840: Dutch Reformed, Presbyterian, Methodist, or Lutheran. The Catholic Church was founded in 1841. Outside the hamlets, the land was divided into farms, large and small. The farms were divided and bounded by all kinds of fences: stone, rail, board, with gates of all sorts.

In the 1840 federal census, 491 people worked in agriculture, 454 in manufacture and trade, and 16 in commerce. Some of those in manufacture and trade were women, but this census lists only the names of the heads of household and numbers of people in the occupations, so it is possible to tell only by inference. For example, if three people in a family worked in manufacture and there were only two males, one of the females must have been working in a mill. The same would be true for female farmers, of course.

I had always thought about 19th century Schaghticoke as an agricultural community with a little industry, but this even division of occupations proves that wasn’t so. I have written before about the industrial revolution in Schaghticoke. Besides the mills listed in Grant’s Hollow and Schaghticoke Hill, there were textile, saw, and grist mills in the gorge of the Hoosic River at Schaghticoke, and at the falls between Schaghticoke and Valley Falls. There were also seasonal flax processing, saw, cider, and grist mills on the Tomhannock Creek and other small streams throughout the town.

The census also listed nine “learned professors and engineers” in town, and in a connection to the past, five Revolutionary War veterans. I thought it might be interesting to learn a little about those folks. I’ll begin with the Revolutionary War vets. They were Peter Ackart, 84; Elisha Phelps, 82; Nathaniel Robinson, 82; John L. VanAntwerp, 80; and John Welch, 77. By the way, there were only six men over 80 in the whole town, and four of them were Rev War vets.

John Welch was the head of a household in the 1840 census, probably including his wife, plus 1 male aged 20-29, one female aged 10-14, and three females aged 15-19. They young people are young enough to be grandchildren rather than children. As the household includes four people working in manufacturing and trade, this means that at least two of those people were women, if John was still working, if not, then three.

Thanks to a hint on ancestry.com, I discovered the Revolutionary War pension application of John. He was born in 1763 in West Windsor, Connecticut. Though the pension application says he served in the Connecticut line, his testimony does not reflect that. He says he enlisted in Colonel Marinus Willett’s NY Regiment on April 1, 1782. He served at a small fort in Ballston for several months, part of the garrison, and spent time cutting trees around the fort to ensure a field of fire. He then went to the Schenectady Barracks for a couple of months, receiving an honorable discharge on January 1, 1783.

After the war, he moved often, spending most of the time in Ballston Spa. He also lived in Norwich, Chenango County, and Palmertown, Milton, and Malta in what became Saratoga County. He spent from 1828-1833 in the town of Schaghticoke. He doesn’t mention his family, but he married Dorcas in 1816 in Ballston. She was considerably younger, and received his pension after John died. Orrin Pier of the village of Schaghticoke preached his funeral sermon on December 5, 1841. John was buried in the Old Schaghticoke Cemetery- the one between the Catholic Cemetery and Elmwood Cemetery on Stillwater Bridge Road. Dorcas died in 1861, aged 76, and is buried there as well.

Elisha Phelps was married to Clarissa, a sister of Dr. Ezekiel Baker, the prominent local doctor who died in 1836. According to Ezekiel’s probate file, they lived in Cambridge. By the 1840 census, Clarissa had died, and Elisha was living with Freeman Baker and his family. I am not sure how Freeman was related to the many other Bakers in town, but I don’t think Elisha and Clarissa had any children, so he was probably a nephew or great-nephew. The family included 1 male under 5, 1 26-29, 1 30-39, Elisha, and 1 female under 5, two from 5-9, and 1 from 20-29. Two people worked in agriculture, probably Freeman and the other young man. There is an Elisha Phelps in the pension roll for NY for 1833, and after several tries, he was approved for a pension based on his Revolutionary War service.

In his pension application of 1832, Elisha was born in Hebron, Connecticut in 1759. The Connecticut birth records state it was 1758. He said he was drafted into service for three months there on September 5, 1776, into a company of Connecticut militia commanded by Captain John Howell Wells. They marched to Westchester, NY, where Elisha was on duty as a sentinel when British General Howe’s army landed at Frogs Neck on October 18. He fought in that battle as they retreated to New Rochelle, Rye, and Merrimack. The whole company was discharged on December 5.

Elisha was drafted again at the end of May, 1777 for two months into a different company. He worked at Fort Trumbull, Connecticut for a while, but got sick and was furloughed home. In spring 1780, Elisha moved to Cambridge, Washington County, N.Y. There he was drafted into a company commanded by Captain Adiel Sherwood and spent two months at Fort Ann doing garrison duty. Unfortunately, the pension application does not mention his wife. One of the people testifying on his behalf was Truman Baker, brother of Clarissa.

Nathaniel Robinson, 82, lived in town with just his wife, Susanna Hamblin, as of that 1840 census. However, his son Samuel, born in 1809 here in Schaghticoke, lived next door, with a large family, so at least the old people had some support. According to his pension application, Nathaniel was born in Peekskill in 1759 and enlisted there in 1777 as a member of a Connecticut regiment of the line. This means he was in the regular Army rather than the militia. He was a full-time soldier, while militia men were only called out as needed. His commanding General was Anthony Wayne. Nathaniel was in the battles of Germantown, Monmouth, and Stoney Point, serving for three years. He was wounded in the leg at the battle of Monmouth, and apparently was lame for life.

I first find Nathaniel in the census for Schaghticoke in 1810, though by the evidence of Samuel’s birth in 1809, he had arrived a bit earlier. Ancestry.com family trees indicate Samuel was the youngest son of a large family. By 1819, at age 61, Nathaniel applied for a pension. He was fortunate to have the help of local resident and first judge of the county Josiah Masters. Masters added a note to the application saying, “I am personally acquainted with Nathaniel Robinson and he is very poor and in want of assistance from his country. Indeed both his revolutionary service and poverty is (sic) a matter of common notoriety in this part of the country.” Nathaniel was awarded $8 per month, about $150 per month today. At the time, his two youngest children lived with him and wife Susan. They were Sally, aged 15 and Samuel, aged 10.

As part of the pension application, Nathaniel submitted an inventory of his possessions. He didn’t have to include his bedding and clothes as they were considered essential. He had no real estate, but had vegetables in a hired garden worth $10. He had a 12-year-old cow worth $15, three pigs worth $6, four chickens worth 50 cents, one axe, one hoe, two pails, one iron kettle, four knives, three iron spoons, one pot and a tea kettle, one basin, three bowls, two jugs, one bottle, one tumbler, one churn, one griddle, three cups and saucers, one small spinning wheel, one loom, two shuttles, one broom, two baskets, one shovel and tongs, four plates, one spider, and one iron crane. A spider is a frying pan with legs, for use over an open fire by placing it on a crane. The total value was about $50, and Nathaniel owed about $60. The Robinsons must have led a very basic existence indeed.

perhaps Mrs Robinson made a bit of money spinning yarn.

Nathaniel died in 1842, wife Susanna the following year. They are buried in the Brookins Cemetery, on the west side of Route 40 in the Melrose part of town. I am sure they lived in that part of town. Three wives of Samuel Robinson are buried there as well. Samuel lived on in the area until his death in 1891. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

The last two Revolutionary War veterans in the 1840 census had actually been members of the local militia, the 14th Albany County. Sylvester’s “History of Rensselaer County,” published in 1880, records Peter Ackart as one of the few Revolutionary War veterans remembered by residents to that day. I find this ironic, as I have been able to find out so little about him in the public record. He was definitely born here, probably the son of another Peter Ackart. I feel he was the Peter Ackart, Jr., who was born in 1767. He was a very young soldier, and served with his father in the 14th Albany County Militia. I have found him in the local census from 1790 until his death. As of 1803, he had real estate worth $948 and a personal estate of $157. He was a farmer, and probably lived in the area just to the north of Stillwater Bridge Road, where several Ackart families lived in the 1850’s.

This Peter married Maria Benway, a local girl, born in 1789. Their first child, David, was born in 1807. The couple went on to have seven children in total baptized at the Schaghticoke Dutch Reformed Church, the last in 1826. At least two died young. Peter died in 1845. His tombstone is in Elmwood Cemetery. He must have been buried elsewhere first and reinterred as the cemetery opened in 1863. The 1855 census lists the families of three of his sons: David, Jacob, and John, who all lived next door to each other. Peter’s widow Maria, then 66, lived with Jacob and his family. She died in 1866 and is also in Elmwood Cemetery. So this wife of a Revolutionary War veteran survived through the Civil War. No wonder locals remembered her husband Peter as a vet of the earlier war when Sylvester wrote his history.

John Lewis VanAntwerp, 80, was the final Revolutionary War veteran listed in the 1840 census. He was also listed in Sylvester’s “History” as a known veteran. He lived with one of his sons, Peter Yates VanAntwerp. John was born in Albany in 1760, but moved to Schaghticoke by age four. He enlisted in the local militia regiment in March, 1776, another very young soldier. He served off and on until 1780, rising in the ranks as Ensign, Corporal, and Sergeant, and according to one record, to Lieutenant. When the war started, the Colonel of the 14th Albany was John Knickerbacker, prominent local man. In 1778 John VanAntwerp married Catlyna Yates, daughter of Peter Yates, in Albany. Peter and his family had moved recently to Schaghticoke, and he became the Colonel of the 14th after John was wounded at the battle of Saratoga at the end of 1778. So John L. VanAntwerp must have been quite a guy, becoming an officer and marrying the daughter of the new Colonel before the age of 20.

In his pension application, John described his Revolutionary War service. He served until 1780, “employed in watching and pursuing hostile Indians at Schaghticoke and Stillwater.” He also marched to Lake George, Fort Edward, Fort Ann, and Whitehall. About October 1, 1777, he was part of a company attached and volunteered to General Gates, in Camp at Stillwater. He was there until the surrender of Burgoyne. In 1778 he guarded different forts on the northern frontier. At one point he marched to Fort Ticonderoga to look at British shipping. This matches what I have read of the experiences of quite a few other local men. They served a month to six weeks each year of the war, as needed.

John and Catlyna had a number of children. Five were baptized in the Schaghticoke Dutch Reformed Church, starting with Alida and ending with Peter Yates in 1794. Catlyna’s father, Peter Yates, the Colonel, died in 1808. He was a wealthy man with a number of children. Catlyna received household items from his estate, plus a silver table spoon, a silver ½ pint cup, a mare, a cow, and a bushel of salt. She also received 200 acres of land in Montgomery County, and 100 pounds. Unfortunately John does not appear in the early New York State assessment rolls, from 1799-1804. I would love to know if he used his wife’s inheritance well. What happened to the property in Montgomery County? I feel the family lived in the area north of Stillwater Bridge Road, near the Ackarts. John was a farmer. Catlyna died in 1810, not long after her father, leaving John as a widower with several teenage children at home.

When John finally applied for a pension, in 1832, he seemed to have to go to very great lengths to prove he had been a veteran. This would seem ironic for the son-in-law of the Colonel of the Regiment. Herman Knickerbacker, son of John, former Congressman, and judge of the county, testified on his behalf, along with the pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church, Peter Ackart, and Wynant Vandenbergh, who with his father tended the ferry over the Hudson River at Stillwater during the war. Wynant said he had seen John take the ferry on many occasions while on duty during the Revolution. Despite all this support, John was dropped from the pension rolls for a couple of years. Job Pierson, another local former Congressman and judge, helped John re-apply and obtain his pension again, in 1837, at which point he was owed $320. When John died in 1848, he left two sons, Peter and John, and two daughters, Sarah and Maria. John and Maria died by 1851, but Peter and Sarah continued to receive their father’s pension. As of the 1855 census, Peter, then 61, was a farmer with wife Mariah and five daughters. He and Sarah both died in 1860. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

So the 1840 census lets us know quite a lot about most of the oldest residents in town. We find that they were well-known in the community. The most prominent residents were ready to speak up for them and the veracity of their life stories. One of them was a destitute old man, despite living near his son, but the others were at least able to live comfortably, and all had family nearby, if they didn’t live with them.

The 1840 census also identifies eight men who were “learned professors, and engineers.” I feel this is a euphemism for people with a college education or the equivalent. The fact of singling out these men, for they are all men, from those working in agriculture and manufacturing and trades, the other two categories, indicates how rare this was in the U.S. in 1840. At least in Schaghticoke, there were no engineers. There were three doctors, three pastors, and two lawyers. At least one lawyer, Thomas Ripley, was not included in the list- he was assigned no occupation in the census, so perhaps there was an error there. Thomas was a graduate of R.P.I. who became a U.S. Congressman a few years later. He certainly was a “learned professor.”

I will begin with the three doctors: Ezekiel Baker, Zachariah Lyon, and Simon Newcomb. Simon Newcomb was born in Nine Partners, near Poughkeepsie, in 1779. He had moved to Pittstown by 1800 with his parents and family. He married Sarah Follett in 1802. They had children William, Nahum, Nomina, Wesley, David, Simon, and Sally, who died as an infant. Sarah died in 1820 and he married Hannah Stover in 1821. They had four daughters: Sarah, Elizabeth, and twins Louisa and Mary. According to “The Genealogy of the Newcomb Family”, written in 1874, Simon lived in “upper Schaghticoke” for about eleven years. The 1840 census captured him in our town during that time, but he was back in Pittstown by 1850. That census found Samuel (sic), 70, with real estate of $3500; Hannah, 57; Eliza, 24; Louisa and Mary, 20. By 1860 they had moved to the Speigletown area, part of the town of Lansingburgh at the time. Simon made it into the 1870 census, aged 91. He had real estate worth $5000, and a personal estate of $11,500. His daughters Elizabeth and Mary lived with him. He died later that year and is buried in Tomhannock. The genealogy notes that he was healthy in body and mind right up to his death. Several of his children lived locally, and his son Wesley also became a doctor. He was a founder of Albany Medical College and an internationally known conchologist (expert on mollusks.)

Simon Newcomb

The family genealogy describes Simon in glowing terms. As I have found with many prominent men of the era, he was active in all aspects of the life of his community: financial, political, and religious, as well as professional, as a doctor. He began his career as a teacher in the local school in Millertown at age seventeen. He joined the Methodist Church about the same time. Unlike the other doctors in the census, he studied medicine with several local doctors, rather than going to college. He apprenticed a year each with Ezekiel Baker, the uncle of the Ezekiel Baker in the 1840 census, David Doolittle, Nehemiah King, and John Hurlburt. He volunteered with the local regiment for the war of 1812, though the men never got to fight. In addition to being a doctor, he was the first postmaster at Johnsonville, a justice of the peace for 27 years, the town supervisor in Pittstown for three years, U.S. assessor for two years, plus town clerk, commissioner of deeds, and overseer of the poor. He was described as being a stern man of firm decision, great integrity, and unpretentious dignity.

Zachariah Lyon was the second doctor in the 1840 census. He is mentioned in several 19th century histories of Rensselaer County as an early doctor in town- but without elaboration. I have pieced together his biography from census and a couple of newspaper articles. He first appears in the local census in 1830, with a family of five, including two immigrants. Presumably the count included him, his wife, Sarah Lavinia, daughter Anna, and perhaps two servants. The 1855 census indicates he and Sarah had been in town for 27 years, which would put their arrival in 1828. That census lists Zachariah as 62 years old, born in Connecticut. Sarah, 65, was born in Vermont, as was daughter Anna, 40. She was born in Sunderland, Vermont, a small town in southwest Vermont. This would indicate that the Lyons moved here from Vermont when Zachariah was 34, Sarah 35, and Anna 13. All of the other censuses indicate Zachariah was born in Massachusetts. Presumably Zachariah came to town as an experienced physician, having practiced in Vermont. Zachariah had arrived at a good time, businesswise, as the established doctor, Ezekiel Baker, was elderly, and died in 1836. In 1837, he and Baker’s nephew, another Ezekiel and doctor, were the two doctors called to examine murder victim Herman Groesbeck, to determine the cause of death, an indication that he was firmly established here.

As with Simon Newcomb, Zachariah was involved in politics. I found him as a delegate to the local Whig conventions in the 1840’s. He was the town supervisor of Schaghticoke in 1854. He was also involved with his church, as one of the founding vestrymen of the local Episcopal Church in 1846. During the Civil War, the government imposed new taxes, and these showed that Zachariah paid 12 cents in tax for four pieces of silver- presumably silverware- plus $1 each for two one-horse carriages. He paid on income of $235 in 1864. To me this indicates a comfortable but not wealthy family. The census consistently shows one household servant. At least one carriage would be necessary for his job as a doctor.

Daughter Anna appears in the census with her parents in all but one census. Sometime between 1855 and 1860, she married Embree Maxwell. He was a farmer from Saratoga County, just a couple of years older than her father. He died in 1863 and is buried near the Quaker Meeting House in the town of Saratoga, according to an article in “The Saratogian” in 1940. Anna and Embree had a child, Frank, probably about the time his father died. The 1865 census found Anna back with her parents, with Frank, aged 1 8/12.

The family was together for the last time in the 1870 census, which listed Zachariah as 78, with an estate worth $18,000, still working as a physician. Sarah was 80, Anna, 52, and Frank 6. Sarah died in 1872, and Zachariah in 1873. This left daughter Anna as his only heir. She received his house and lot plus the income from the rent of a brick store, sheds, and a yard next to his home. This indicates he had lived in the village of Schaghticoke. The Lyons are buried in Elmwood Cemetery. Frank died at age 13, and Anna died in 1892 of tuberculosis. Both are in Elmwood as well. I would love to find out where Zachariah was born, where he was educated, how they ended up in Schaghticoke, how the couple felt when their only daughter married an elderly Quaker farmer, how they felt when they finally had a grandchild.

The third doctor in the 1840 census was Ezekiel Baker. Researching him has caused me all kinds of frustration. At this point, I think that there were three men by that name in Schaghticoke in the first 35 years of the 19th century. The eldest Ezekiel was been born about 1730 in Connecticut. An ancestry.com researcher says he was here as of the 1790 census, with a family of 2 males over 16 and 3 females over 16, but moved on and died in Herkimer County in 1800. His son Ezekiel was born in 1761, and travelled with the family to Schaghticoke, but stayed on, as did his son Truman. I don’t have any way independently of that researcher to be sure of that father and son. But for sure, a man named Ezekiel Baker was in the 1790 census, and then in the 1800 census, Ezekiel shows up with a family of one male from 10-16, 2 from 17-26, one from 27-44, one female under 10, 1 from 17-26, and one from 27-44. I’m not sure who all of those people were, as this Ezekiel and his wife Rhoda had no children. Ezekiel Baker was also one of the first school commissioners of the town, before 1800, and one of the organizers of the Homer Masonic Lodge in 1799.

The Ezekiel Baker of the 1800 census was a doctor. As of the 1803 NYS assessment, he had real estate of $1950 and a personal estate of $257. That same year, he was one of the founders of the Schaghticoke Presbyterian Church and an original trustee. This church was founded by the incoming New Englanders to town, and was THE church of the local mill owners, movers and shakers. When the church was reorganized in 1820, Ezekiel was still a trustee. He purchased pew 18 for $33. Pew purchase and rent was the way the church was financed.

Ezekiel continued to be a pillar of our community until his death in 1836. The more I look at early deeds for the town, the more land I see that he owned. For example, the 170 acres of the current Howard Gifford farm was sold by Ezekiel to Josiah Masters before 1815.Of course he continued to appear in the census. Interestingly, in 1810 and 1820, his family included one female slave. I would love to know why Ezekiel and his wife purchased a young black girl (she was from 18-26 in the 1820 census). She remained with the couple in the 1830 census, though by then, of course, she was free.

The probate file of Ezekiel listed his many heirs: his brothers Lyman, Truman, and sisters and their many children. The most important one for us is Ezekiel, a son of his brother Truman. Ezekiel stayed on in Schaghticoke. I’m sure that to avoid confusion, he was always known as Ezekiel 2nd. to differentiate him from his uncle. He was the doctor of the 1840 census. Incidentally, that census entry includes one free black woman of the age to be the same who had been his uncle’s slave.

Ezekiel Baker 2nd was born in 1795 in Pittstown. He attended Williams College from 1810-1814, and was listed as M.D. in the class of 1810, though apparently he did not graduate. Perhaps he mentored with his uncle Ezekiel to become a doctor as did Simon Newcomb, another of the 1840 census doctors. According to Anderson’s “History of Rensselaer County,” he was a local doctor for fifty-one years.

Ezekiel picked up right where his uncle left off, becoming a pillar of the Presbyterian Church. He was secretary of the meeting when it reorganized in 1831, was a clerk of the trustees for many years, and first president of the Sunday School. Ezekiel was also involved in local politics, attending Whig conventions in the county. He ran for state assembly and county coroner in the 1840’s and 1850. Anderson states that he was a strong abolitionist, and that his home was a stop on the underground railroad in the 1850’s. And he got involved in business matters as well. Apparently he was one of a group of investors who held the mortgage on extensive mill properties of Ephraim Congdon on the Hoosic River. Ephraim defaulted in 1834, and the investors sold the property at auction.

Ezekiel was married to Harriet Bryon Bryan of Schaghticoke. They had six sons. David Bryon Baker, born in 1821, attended both Union and William Colleges. He was a doctor, but also town clerk of Schaghticoke as a young man, in 1843-1844. I’m sure he was tapped to be his father’s successor as town physician, but he died in 1847. He was married to Jenette C., and they had two small children. One of them, Calot, lived with his grandparents for a number of years.

The Baker’s second son, Charles, was born in 1823. Charles became a general merchant, and worked for local mill owner Amos Briggs. He was in business in Schaghticoke until his death in 1896. Third son Robert was born and died in 1825. The fourth son, Lorenzo Dow, was born in 1826. Though he became a merchant like brother Charles, he was also a tailor and concentrated on selling clothing. He must have been a bit more outgoing than Charles, or maybe more successful, as he rated a biography in Anderson’s “History of Rensselaer County.” Thus I know that he attended both the Greenwich, NY, and Manchester, Vt. Seminaries- the equivalent of high school- and then went on to work in Troy for a few years. Lorenzo returned home to become a clothing merchant and tailor in the village of Schaghticoke for the rest of his life. He was also the town clerk in 1853-54, and held various positions in the government of the new village of Hart’s Falls (Schaghticoke) after 1867, as did brother Charles. Lorenzo was very successful, building the Baker Opera House about 1875. It had retail spaces on the first floor- including his own and his brother’s- and a theater upstairs, and was located where Sammy Cohen’s is today. Unfortunately it burned in a huge fire in 1880. Lorenzo survived until 1904.

Fifth son William Henry was born in 1829. He was listed in the 1850 census for Schaghticoke with his parents, and brothers Lorenzo, and John as a merchant, age 21. By the 1855 census he was gone, probably to Racine, Wisconsin, where he was listed in the 1860 census as a bookkeeper, with wife Mary and two small sons. He died before 1866, as he was listed in his father’s will as deceased.

Youngest son, John Ezekiel, was born in 1831. Though John studied medicine at Williams College, he also attended Union Theological Seminary in 1858 and became a Presbyterian Minister. I wonder if there was pressure for John Ezekiel to become a doctor as his oldest brother David Bryan had died. If so, John evidently persisted in the career for which he felt called. He moved to Rochester, where he was a minister and prominent member of the community, living until 1894.

Father Ezekiel lived until 1866, long enough to see the death of two of his sons, and the success of the rest. Widow Harriet survived until 1872. All of the Schaghticoke Bakers are buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

Returning to the 1840 census, it also included three ministers in the list of “learned professors and engineers.” They were Hugh M. Boyd, Hawley Ransom, and J. H. Noble. I will begin with Hawley Ransom, as I know the least about him. He was born in Vermont in 1809. According to Sylvester’s “History of Rensselaer County,” he was an original member of the Troy Conference of Methodist Ministers in 1834, at which point he was serving at Schaghticoke Hill. That is the little community on Route 40 just south of where it is crossed by the Tomhannock Creek. Hawley served as the justice of the peace in the town of Schaghticoke in 1843.He and wife Lucy moved to Northumberland in Saratoga He must have felt quite a tie to the place, as when his first wife, Lucy, died in 1858, he had her buried in the little cemetery next to the church, even though he had moved to Northumberland in Saratoga County. The couple had stayed in Schaghticoke for a long time- at least from 1834 to 1855, as the 1855 census for Northumberland states that Hawley and Lucy had lived there for just two months. Oddly, Hawley, now 50, was listed as a shoemaker. Wife Lucy was also 50 and their two daughters, Margaret, 24, and Drucilla, 15, lived with them.

By the 1860 census for Northumberland, Lucy had died, and Hawley had remarried Catherine Strong. Hawley was again listed as a clergyman. He and Catherine, 35, lived with Abby, 20- presumably Drucilla called by a different name, and Harriet Strong, 40. She was Catherine’s sister, a milliner. The 1865 census shows the birth of a daughter, Josephine, to the couple, then 11 months old. This census lists Hawley as both farmer and minister- and this was probably the case in the censuses where he was listed as a shoemaker and farmer alone. Hawley died in 1873 and is buried in the Reynold’s Corners Cemetery in Moreau. Wife Catherine died in 1896 and is there as well.

Hugh M. Boyd was probably born in Schenectady in 1795. He graduated from Union College in 1813. He is listed in a book of the graduates of Union as a clergyman from Schenectady. As would befit a man from very Dutch-oriented Schenectady, Hugh was a Dutch Reformed minister. I don’t know where he was from 1813 to 1830, but I think he was in Saratoga as of 1830, based only on a census listing. Hugh was the pastor at the Schaghticoke Dutch Reformed Church from 1835-1841. During that time he and his wife Mary Dorr had two daughters. Margaret was baptized in 1835 and Martha was born in 1836 and baptized April 30, 1837. This was a time when the church, the oldest and once the largest congregation in town, was shrinking. He did marry 23 couples during that time, including one black couple, and baptized 25 children. After he left in 1841, it was seven years until another baptism was recorded. I don’t know where Hugh went after he left Schaghticoke, but he died in 1847 at age 52 and is buried in Vale Cemetery in Schenectady.

The third minister in the 1840 census is Reverend Dr. Jonathan Harris Noble, known in the records as “J.H.” He was the minister at the Schaghticoke Presbyterian Church from 1837-1869. He was born in Vermont in 1804, the son of Obadiah, whom I think was also a minister. Jonathan was a graduate of Williams College in 1826 and the Princeton Theological Seminary in 1829. I’m not sure where J.H. was in the years before he came to Schaghticoke, though his interment record states he was in Tinmouth, Vermont at some point, but he arrived here as an experienced minister. This was good for the church, as it had been suffering through schism in the previous ten years. J.H. brought stability. Unlike other prominent local men, J.H. stuck to his job, not getting involved in politics. This included participating in the larger Presbyterian synod and the national home and foreign missionary societies. Mrs. Noble participated as well. I found her listed in several publications of the American Tract Society in the 1840’s, for example, which published the pamphlets used by foreign missionaries.

That 1840 census includes J.H., and his wife Octavia, plus one other female aged 30-39, probably her sister Emily, plus one female age 10-14, presumably their daughter Mary Louisa. The 1850 census shows Jonathan, then 46, with his wife Octavia Porter, 43, her sister Emily, 50, and their mother Aurora, 85. I don’t know where Mary Louisa was. She appears in the 1855 census, aged 22. She had joined her father’s church the year before. Emily and Amanda Porter continued to live with the family. Johnathan also appeared in the 1855 NYS census as a farmer. He had twenty improved and ten unimproved acres worth $4000. He had grown seven acres of oats, two acres of corn and ten acres of potatoes the preceding year. He had 23 fowl, one cow, and one pig. So he primarily grew what his family needed. Mary Louisa was also left out of the 1860 census, when J.H. and Octavia lived just with a servant, and in 1865, when the church records indicate she moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Around the same time, in October 1865, the Albany Presbyterian Synod held its meeting in Schaghticoke. This must have been a real feather in J.H.’s cap. Unfortunately, his wife was ill and dying at the time. An article in the Troy “Daily Times” records that J.H. was amazing, being the good host of his fellow ministers while tending to his ill wife. Octavia is buried in Elmwood Cemetery. J.H. remarried, to a woman named Caroline, by November 1866, when she joined the Presbyterian Church.

The minutes of the Presbyterian Church session reveal that Rev. Noble proposed to resign in fall 1868. It took until the following June to find a replacement. This is reflected in the 1870 census for Schaghticoke, when J.H., now 65, and wife Caroline, 45, were living in the inn of Garrett Groesbeck, rather than in the brick manse. But J.H. did not retire. He went to Johnsonville by 1871. The Presbyterian Church had begun there in 1856, but I found J.H.’s name in a Presbyterian record of home missions in 1874. I’m not sure why the assignment in Johnsonville would be considered a mission, when it was already established. I did not find the Nobles in the 1880 census, but J.H. was still listed as being in Johnsonville in a newspaper article of 1882.

Sometime later, J.H. and Caroline Noble moved to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, presumably drawn by Mary Louisa living in that state, though there was a Ministers’ Home there, for retired pastors. J.H. and Caroline were living there when he wrote a letter to the local Synod, meeting in April 1896. J.H. died later that month. He was buried from the Presbyterian Church in Schaghticoke, with seven fellow ministers taking part in the service. The 1900 census found Caroline in the Westminster Home in New Jersey. She died in 1901. Both are buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

Returning to the 1840 census, there were two lawyers among the “learned professors and engineers. I have already written extensively about one of them, Herman Knickerbacker. He is one of the most famous residents in the history of the town. Unfortunately to me, this is because he was the model for Diedrich Knickerbacker in Washington Irving’s “Knickerbocker’s History of New York.” But he was also one of the first lawyers in town, U.S. Congressman from 1809-1811, Rensselaer County judge, and local businessman and mill owner. Virtually every deed involving Schaghticoke in the first forty or so years of the 19th century has Herman’s name in it somewhere, either as the lawyer handling the deal, a witness, or judge.

The second lawyer in the census was Nelson Moshier. He was born in 1806 in Dutchess County. He married Catherine Tice of Brunswick in 1833 at Gilead Lutheran Church. He was the Schaghticoke Town Clerk in 1841 and a school commissioner about the same time. I have found Nelson as the lawyer in probate files and wills of the era. By 1850 the family had moved to pioneer in Michigan. According to a biography on the find-a-grave website, he practiced law there and was a circuit court judge, and the first prosecuting attorney when Isabella County, Michigan was formed. Nelson died in 1872 and is buried in Isabella County. I would love to talk to Nelson about his motivations for moving West. It was certainly becoming more and more common at the time.

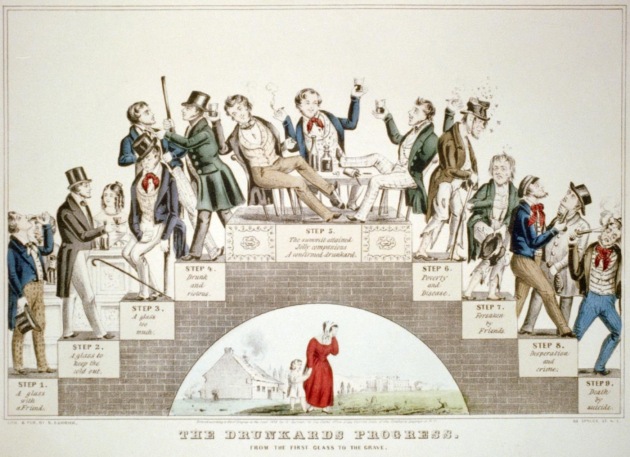

So now I’ve written about some of the more prominent people in town. How about the others? Let me turn to the nine black families. New York State’s gradual abolition of slavery had ended in 1829. While there were 343 blacks in Schaghticoke in 1790, by 1820 there were 66 slaves and 30 free blacks, and by 1830 there were just 52 free blacks. The total of 76 in the 1840 census is actually a bit of an uptick. In a few cases, freed slaves stayed on in the families where they had been owned. For example, the elder Dr. Ezekiel Baker had had one female slave in 1820 and had one freed black female in 1830.

The nine black families in the 1840 census amounted to just over a third of the blacks in town. Interestingly, none is listed with an occupation, though they certainly all worked! As you will see, in most cases I was unable to find out much, if anything, about the families. This is partly because they were often illiterate, they were not taxed, and were not active in politics. They also moved a lot, and lived in poor circumstances. They just weren’t much in the public record. The heads of household of these black families were Thomas Mando, Prince Jackson, Peter Williams, Thomas Robins, Peter Baker, James Hornbeck, James Franklin, Stephen Calvin, and Joseph Winney.

I do know a bit about one of the families. There is a legend that Thomas Mando, who was listed in the census as over 55, with a female over 55 and one male under 10 in his family, may have been “Thomas Mandolin”, a former slave of the Knickerbacker family. He got his surname because he played the mandolin. What is true is that he and his wife had also been a family in the 1830 census, right after the final abolition of slavery. At that point they had four children living with them. It is possible that the young boy in the 1840 census was a grandchild. The couple was still in the 1850 census: Thomas, 83, and wife Hannah, 60. Thomas still listed his occupation as laborer, and they had a black girl named Margaret Fonda, 8, living with them. One of their sons, also Thomas, and his wife Catherine and family were still in town as well. Their youngest child, Albert, then 4, became a composer and orchestra leader in New York City. I do not know where the elder Thomas Mando and his wife are buried, but the younger Thomas, wife Catherine (Katie), and several children, including Albert, are in the Methodist Cemetery at Schaghticoke Hill.

Prince Jackson and his wife were also in both the 1830 and 1840 census. In 1830, he was between 24-36 years old and she, 10-24. In 1840 they were both listed as between 35-55 years old. In 1830, there was a second black Jackson family, that of Richard, with a family of four, but he was gone by 1840. And Prince and wife were also gone by 1850. Prince is a fairly common name for slaves, as was Jackson, so there were a half dozen men with that name in the New York area in 1850. I don’t think any of them was our Prince. So I will have to leave his story there.

Peter Williams is another black man who also appeared in the 1830 census. At that time, his family consisted of him, age 24-36, his wife, age 10-24, and a son under 10. The 1840 census listing is similar, with one male 24-36, one female 10-24, but this time one female under 10. There are definitely some issues with the accuracy of their ages. The Williams stayed on in town, and the 1850 census lists them as Peter, 45, a laborer born in New York, illiterate; his wife, Diana, just 23, also born in New York; and their son John, 3. This clearly was a second wife for Peter. That census also included Harriet Williams, a black girl aged 16, who worked for the family of Ormon Doty, and Nancy Williams, a black woman aged 27, who worked for the family of John Groesbeck. They could have been daughters of Peter. Nancy was still working for the Groesbecks as of the 1855 census, though her age was then listed as 41. She was born in Rensselaer County.

I did find that Peter and Diana moved to Waterford by 1860. Peter, now 55, and Diana, 28, had a daughter Sarah, 9. Peter was a laborer, with a personal estate of $15. But I could not find them after that. It seems like a number of children passed in and out of the census listing for the couple. It is so difficult and frustrating to trace these people, handicapped by their race and their illiteracy, when we would love to know the whole story.

Thomas Robins was the last black man who appeared in both the 1830 and 1840 census. In 1830 his family included two males under 10, and one 36-54- that was Thomas- plus one female under 10, one from 10-23, one from 24-35, and one from 36-54. One of the older women was certainly his wife, but there must have been another woman who was neither child nor wife, plus perhaps three children. By the 1840 census, the family was reduced to just Thomas and his wife, both listed as over 55.

There is quite a twist by the 1850 census, when there was a Peter J. Robbins, a black man aged 35, working as a laborer on the Kenyon farm. Peter stayed on in town and served in the Civil War, returning by the 1865 census, when he was now listed as a 55 -year -old laborer, with a wife and young son. Peter could certainly have been one of the sons of Thomas. I cannot find Thomas and his wife for sure elsewhere in the 1850 census, as there are several couples with Thomas Robins as the head of household of the correct age in New York State.

Peter Baker was another black man with a family in the 1840 census, though not in 1830. He was aged 24-35, and had a wife in the same age range, plus one daughter under 10. I feel this family had left town by 1850 and moved to Lansingburgh. In that census there was a Peter, aged 35, with wife Susan, aged 33, and daughter Mary, aged 14. I could not find them in the 1860 census, but in the 1865 NYS census, they were in the 1st Ward of Troy. Peter was a coachman, who had been married three times. His wife was now Sarah, aged 43, listed as a mulatto, while Peter was black. She was born in Maryland, and this was her second marriage. Interestingly, a 40-year-old black man named Ebenezer Williams, a barber aged 40, lived with them. Could he have been another son of Peter Williams, our previous subject?? And another black family which had lived in Schaghticoke, the Hornbecks, lived next door. Unfortunately, I can’t find Peter past 1865.

James Holenbeck or Hornbeck, also black, had a family of four in the 1840 census. He was from 24-35 years of age, his wife the same age range, plus one son and one daughter under 10. There are graves in the old Methodist Cemetery at Schaghticoke Hill- the same cemetery where the Mandos are buried- for Emeline, died May 8, 1847 age 7; and Henry, died May 12, 1847, age 18, both children of James and Susan Hornbeck. What a tragedy for the family. I feel that they moved to Troy soon after. Though I have not been able to find him in the 1850 or 1860 census, a James Hornbeck is in the Troy City Directory from 1857 on, listed as a porter who lived at 38 Fulton Street. The August 20, 1856 issue of the Troy “Daily Times” reported that James Hornbeck assisted the chairman of a “meeting of colored persons” at the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy. The meeting discussed propositions for blacks to get to right to vote, among other issues, reporting on a larger convention held recently in Seneca Falls.

There is also a Joseph Hornbeck in both the 1850 and 1855 Schaghticoke censuses. In the former he was a 12-year-old black boy, who lived in the family of Nathan Overocker. In the latter, he was a laborer in the family of William Brown. He could have been a son of James. As I mentioned above, I did find James Hornbeck and his family living next door to Peter Baker in Troy in the 1865 census. James, 65-years-old, was a laborer. He had a wife, Susan, age 64, born in Rhode Island, who had had eight children. A black couple, Thomas Moore, 26, born in New Jersey, and Rebecca Moore, 27, born in Saratoga, lived with them.

By the 1870 Troy directory, James had died. Mrs. James Hornbeck lived at 119 Church Street. A Joseph Hornbeck lived in Troy as well. This listing for Mrs James is interesting as an obituary in two local newspapers reported the death of Susan Hornbeck in 1864. A post on the webpage of the Lansingburgh Historical Society quotes: “A centennarian with ten years to spare, died at Lansingburgh yesterday. Susan Hornbeck, better known as “Aunt Susan,” was her name. She had attained the age of one hundred and ten years. The deceased was a colored woman—born a slave in Saugerties [Ulster County], and held by the family of John Brown in Lansingburgh for many years—only being released when New York became a Free State.”Schenectady Daily Evening Star and Times. April 9, 1864: 3 col 2.

Albany Morning Express. April 11, 1864: 3 col 3.

James Franklin and his family also lived in town in 1840. James, aged 24-36, and his wife, aged 24-36, had two daughters, one under 10, one aged from 10-14. He was still here in the 1850 census: James, aged 40, a laborer born in New York, with wife Betsey, aged 28. If the ages are correct, this could be a different wife. What happened to the children? I have been unable to find James after this date.

I have been unable to discover anything more than their listing about two of the black families in the 1840 census. Stephen Calvin, a black man aged 36-55, and his wife, the same age, also lived in Schaghticoke as a family in 1840. The last black family in the 1840 census was that of Joseph Winney. Joseph was from 24-35 years old. He and his wife, the same age, had three small sons, under 10 years of age.

Unfortunately this census doesn’t indicate foreign born citizens, which would have been helpful to fill out this story of life in Schaghticoke in 1840. I know that the population of foreign born increased rapidly during this period, mostly due to an influx of mill workers and of Irish immigrants. There were enough Irish Catholics here for the Albany diocese to begin a church in 1841.

Now that I’ve discussed some of the individual families in town, I’d like to move on to discuss how people lived. Beyond generalities, I will use inventories of their estates from probate files to try to figure that out. The problem with this method is that inventories can be more or less complete, but I can’t think of a better way. In 1840 as now, there would be quite a range of prosperity. Earlier in this article, I gave the inventory of Revolutionary War veteran Nathaniel Robinson, whom we would hope was at the poorest end of the range. He owned no land, possessing just a few animals, a few dishes, and a few cooking utensils. Tellingly, his wife had a spinning wheel and a loom. She could process her own wool and make fabric, either for home use or to sell, impossible to know from the information given. The Robinsons certainly lived simply, cooking their food in the now old-fashioned way, over a fire outdoors or in a fireplace, getting water from a well, lighting with a candle or oil or grease lamp. They grew their own food as much as possible, and lived a simple life with no books, pictures on the wall, curtains at the windows, or rugs on the floor.

At the other end of the scale, was Munson Smith, a prominent local businessman and mill owner, who died in 1842. I have written of him before- it’s on my blog at www.schaghticokehistory.wordpress.com. Using the inventory of his estate in his probate file, we can intuit that the Smiths lived in a carpeted home, with curtains at some of the windows and inside shutters on others. A lot of the furniture was mahogany, with matching chairs at the dining table. They had large sets of matching dishes (39 plates in one set!!), with specialized dishes for gravy, custard, fruit, and other foods. While there was some plain glassware, some was cut glass, and they had specialized wine glasses. Some of the silverware had ivory handles, some was silver.

astral lamp

Several bedrooms were furnished with maple, mahogany, and cherry beds, small tables, chairs, and dressers, with a mirror on each wall, and lots of bed linens of different types. This was in the pre-bathroom era, so there were several wash bowl and pitcher sets, for washing in the bedrooms. While there were fireplaces, the rooms were also heated with cast iron stoves, probably set into the fireplaces and using their flues. There were candles on the mantelpieces, but they also had the latest Astral lamp. There were also several clocks. The inventory lists the kitchen stove, plus pots and pans of brass, tin, and iron. The kitchen range with a cook top was a relatively recent advance over open hearth cooking. It may have been either coal or wood burning.

Munson’s office was either in or attached to his house. It contained office furniture, plus a bedroom, furnished, and his library of about 60 volumes. This was a substantial library for the time. Munson’s wearing apparel is not itemized in the inventory, but was valued at $21. This doesn’t seem like much, but considering that the kitchen stove was worth $12, it is quite a lot.

I’ve been trying to find an inventory of a less wealthy person who was not a farmer to contrast with Munson Smith. This is not easy to do. I did find that of Henry Thompson, who died in town in 1845. He left a widow and five children, two under 21. His widow Sarah stated his “goods and chattels” were not worth more than $250. Henry left one cow and one swine, and there was some basic agricultural material, a scythe, a straw cutter, a potato hook, a plough There was one horse, two wagons, two “cutters”- sleighs, a saddle and harness of different kinds. This would have provided transportation for the family and his business. He also had the tools of a carpenter: a cross cut saw, grindstone, six planes, an adze, chains, a square, five moulding tools, a set of framing chisels, a hammer, a broad axe, a circular saw, a smooth plane and gauge, plus some wood: two sets of boat plans, a lot of birch planks, and another lot of planks. Was he a carpenter who built boats?

Henry’s widow retained a wagon, two stands, a rag carpet, a bureau, a table, six chairs, and a looking glass as her widow’s portion. The rest of the household furniture consisted of just four beds with their bedding, two stoves, cooking utensils not detailed, one table, six chairs, six knives and forks plus other crockery, one spinning wheel, and library and school books. I’m glad to see the books, as the rest of the furnishings seem basic to say the most.

I did find widow Sarah in the 1850 census for Pittstown. She was 47 years old, born in New York, and had real estate worth $600. In her household were her sons Peter, a 20 -year-old carpenter, Isaac, 10, and Bryan, 6, and a Michael Thompson, 43, born in Ireland, who was a laborer- perhaps her brother-in-law. So I think Henry was a carpenter, and probably an Irish immigrant, who died when his youngest child was just one. She had moved, but not far, and had a place to live.

Let’s look at the probate file of John Baucus, who died in 1832 at 59. He was a farmer who lived near the current town hall. He and his family attended the Lutheran Church, and he is buried in the cemetery at the junction of Melrose-Valley Falls Road and North Line Drive. In the 1830 census for Schaghticoke, John, age 50-59, had a wife the same age plus one son from 10-14, two from 15-19, one from 20-29, and two daughters from 10-14. The inventory of his estate gives us insight into a prosperous farm of the period. He had nine horses, seven cows, four young cattle, four calves, and a pair of oxen, plus 50 sheep, 15 pigs, 18 hogs, and one boar, 13 geese, and some chickens. At that time, there was a woolen mill in the village of Schaghticoke, a market for the wool.

Turning to farm equipment, John had five ploughs, a fanning mill, two ox carts, three sleighs, an ox sled, three wagons of different kinds, two drags, five pitch forks, two dung forks, four rakes, a patent rake, a stone boat (for moving stones), four hoes, some shovels, and other miscellaneous tools. John also left large quantities of hay, stored in several different barns, 500 bushels of corn, 300 bushels of wheat, “a lot of oats in the barrack,” potatoes “in the hole” and 100 other bushels of potatoes and 15 bushels of buckwheat. A barrack is a temporary barn structure. I feel that potatoes were stored in a hole constructed for that purpose, like a root cellar.

plowing at the Farmers Museum in Cooperstown

John’s widow was allowed to keep items apart from probate that were essential for herself and her “infant children” to live. There were five children in this category. She kept ten of the sheep, one cow and four pigs, plus the only household furnishings included in the inventory. There were kitchen utensils- pots, a brass kettle, a frying pan- plus two stoves, 25 chairs, six tables, and four looking glasses. There were seven beds, 30 blankets, 15 pairs of sheets, and 15 pairs of pillow cases, plus two sets of curtains, two carpets, four other window curtains, eight table cloths, one stand (small table), a wooden clock, and a bureau (dresser). This seems like plenty of chairs, mirrors, and bedding, but too little clothes storage, although there were two chests and two cupboards- but they might have been for food or dish storage.

Mrs. Baucus had two sets of dishes, one fine, one every day, two sets of knives and forks, two decanters, six tumblers, and 15 wine glasses. A stove for cooking is not mentioned, though there is a furnace. I am not sure what was meant by that- certainly not what we would think of as a source of central heat. It could have been a stove for heating flat irons. The only lighting implements on the list are three candle sticks, though there could have been various kinds of oil lamps. There were also a churn and a wash tub. The inclusion of a loom, two big and one small- spinning wheels- plus 35 yards of yarn, 44 yards of cloth, and eight pounds of rolls (probably the rolags from which yarn would be spun), suggest household manufacture from the fleeces of those sheep. The family also had two Bibles and twenty other books. To us this would seem like a pretty short list of household goods for a family of eight compared to the extensive inventory of farm equipment, the harvest, and animals, but it was a different time.

Elijah Bryan was another farmer in town. He died in 1842 aged 79. His wife had died the previous year. They lived south of Hemstreet Park, probably near where they are buried in a little cemetery near the junction of River and Pinewoods Roads. While his inventory presumably reflects that of a couple mostly retired from farming, it does reveal how they lived. And there is a pretty good list of Elijah’s wardrobe. He had nine cotton shirts, four woolen shirts, three pairs of linen trousers, a pair of pantaloons, three pairs of woolen drawers (boxers), vests, one coat, a cloak, 15 pairs of stockings, two pairs of boots and one pair of shoes, two hats, two walking canes, and one silk handkerchief. I am not sure of the difference between trousers and pantaloons. This seems like lots of stockings and not enough handkerchiefs. Of course we can’t know the accuracy of an inventory from 150 years ago, and it does lists two separate lots of “old clothes,” which might balance things out.

As to the contents of the house, the inventory includes only candles as the source of light. There are several bee hives and lots of honey on the list, so it’s no surprise that the candles were of beeswax. There was one stove for heating and one for cooking. Most of the cooking and dining utensils were not described in detail, but there were 15 blue plates and six silver teaspoons. Likewise, most of the furniture was not described, except for one cherry table. There were six fancy chairs and six “flag bottom” chairs, plus 12 old chairs. Elijah and Eunice had one looking glass, a Bible, and “a lot of books”, valued at 12 cents. This is “lot” as in a group, not many. There was the equipment for taking care of the clothing- a clothes basket, clothes horse (drying rack), wash tub, and irons, plus food storage- baskets and barrels, kegs, stone pots (stoneware), firkins, casks, and boxes. The house was carpeted to some extent, but it’s hard to tell how much as the list has “1 carpet the largest,” valued at $2.00 and “1 carpet the smallest,” valued at $3.25.

flag-bottom chair

The bedding in the house reflected the house when Elijah and Eunice’s children were home: several bedsteads, three feather beds, four straw ticks (alternative mattress, not as comfortable as feathers), plus 30 linen sheets, 17 woolen sheets, and 1 cotton sheet. I think Eunice must have enjoyed textiles, as the inventory includes a number of “coverlids”: two carpets, two blue and white, two red and white, and one black and white, plus three quilts and three comforters.

The couple had just one horse and one heifer, and, interestingly, “one half of a 1 horse wagon.” Perhaps the wagon was shared with a son or daughter? There were just a few tools: a hoe and a bog hoe, a scythe, a cross cut saw, and an axe. As I said, they must have been mostly retired from farming, so perhaps there were more animals a few years earlier. Certainly Mrs Bryan must have had some chickens.

Next let’s look at the inventory of Eliphel Gifford, widow of Caleb. She died in 1838 and is buried in St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in Melrose. Caleb died in 1817, so she had been on her own for a long time. She had two cows, a boar and 12 sows, ten chickens- identified as “dunghill fowl”, and a pair of geese- kind of a basic set of animals for daily use. There was hay and corn to feed them. She had some potatoes, vinegar, “a lot of pork in the barrel,” apples, and “a lot of lard,” plus equipment to store and process food: stone jars, baskets, 13 milk pans, pails, iron pots, tubs, hogsheads, a cheese press- needed for making cheese, and three flour barrels. She had “a lot of soap”- indicating she made her own, as probably most farm wives did. Eliphel also had both a parlour stove, “one premium stove No. 3”, and a cookstove, plus lots of wood already cut. These stoves place her in the modern world- heating and cooking with stoves, rather than fireplaces. Her bakeware was made of tin, brass, and iron. She had five wooden bowls and two sugar boxes. There was no detailing of any special dishes or silverware, no mirror, no clock, no carpets, and just three books- a Bible and two others.

We hope her children had already taken the furniture they wanted by the time the inventory was taken, as the furniture consisted of just one rocking chair, one stand, one table, one cot, one bedstead, one set of homemade curtains, and one lantern. There were no other lighting devices on the list. There were four cotton sheets, four pillow cases, two calico quilts, one comforter, and two flannel sheets. There was a separate listing of a bed and bedding, valued at $15, the highest valued items on the list outside the livestock.

The appraisers made a list of the “wearing apparel of the dead:” five gowns, three short gowns, three petticoats, two check aprons, three pairs linen stockings, two pairs woolen stockings, nine handkerchiefs, a “bandbox hood ,” five caps, one pair of stays (a form of girdle/bra), one woolen shawl, one velvet cloak, five chemises, and one white cotton chemise. Again, one hopes her children had taken some of her clothes, as there are no shoes on this list, and some very old-fashioned garments- a set of stays, and chemises- which were like today’s slips with sleeves. The short gowns and petticoats would go together, the petticoats being outerwear and not underwear like today. Those are 18th century terms, however. It is possible that Eliphel, as an elderly lady, preferred to wear old fashioned clothes. I do not know what a “bandbox hood” might be, though there were 18th century hoods with interior hoops that might be stored in a bandbox- what we might call a hat box.

The inventory of the estate of Alexander A. Miller, who died at age 27 in 1826, also lists his wearing apparel. This young man, who left a widow and small daughter, was a non-commissioned officer in the local infantry regiment in the New York State Militia. It seems from the inventory that he was a farmer, though it also lists a set of blacksmith tools. Except for a wagon, the most valuable thing in his estate was a cloak worth $40. His uniform cloak with epaulette was worth $20. He also had a sword, sash, and military hat, plus a feather- probably for the hat. He owned four pairs of pantaloons, three broadcloth coats, and a blue surtout coat (also called a frock coat, probably knee length), an old black silk vest, an old hat, two pairs of old shoes, and another cloak, this one worth $12, also seven shirts and six cravats (like ties), a pair of gloves and a pair of mittens, five pairs of socks and one pair of suspenders. Tantalizingly, he also owned a bass viol worth $8. He also had a silver watch, and two pocket books (like a wallet).

Turning to the business side of the inventory, Alexander had five cows and one calf, seven old sheep and six lambs, eight shoats (young pigs) in the pen, 216 fowls, one mare and her colt. He had fifty loads of manure, ¾ ton of hay, 40 bushels of rye, a lot of potatoes in the ground, lots of wood and coal. The most interesting part of the inventory may be that Alexander had been in charge for the past two years of the “committee of the lunatic” which took care of George Miller, a lunatic. George evidently had an estate to pay for his care, but the estate hadn’t reimbursed Alexander for about $650 he had spent. This is a very large sum for the time. After a lot of research, I’ve concluded that George was Alexander’s father. Alexander’s untimely death must have caused even more than the usual grief and chaos. He left a young widow and child, plus the problem of who would take care of his mentally ill father. I’m sure he also left friends and family sad at the death of such a promising young father, citizen, musician, and farmer.

So what can we conclude about life in Schaghticoke in 1840 from this admittedly limited sample? Farm families were as self-sufficient as possible. Inventories show equipment to process and store food, make candles, soap and other basics. Most farms had a variety of animals. Some women processed their own wool and flax at home. At the least they made their own clothes. Most families had stoves for cooking and heating, having advanced from fireplaces. Wealthier families had a few special pieces of furniture and glassware or dishes- for example a cherry table or a few silver spoons. Some of this material may have been heirlooms passed down in the family. While people had small wardrobes by our standards, they owned a few more clothes than families fifty years earlier. Most people had a mirror or two, perhaps a clock, and at least a few books. As to farm tools, most were basic- ploughs, wagons, drags, shovels, etc., but a few new items appeared: a fanning mill, for example. Men had blacksmith and logging tools. Farmers grew the feed for their animals and grain to grind for flour. Some farmers specialized, for example growing sheep for the local woolen mills or lots of poultry, presumably for the local market as well.

Bibliography

Anderson, “History of Rensselaer County”

Baucus, John, probate file, Rensselaer County Historical Society

Bryan, Elijah, probate file, Rensselaer County Historical Society

Find-a-Grave.com

Gifford, Eliphel, probate file, Rensselaer County Historical Society

Miller, Alexander, probate file

Newcomb, John Bearse Genealogy of the Newcomb Family, Elgin, Ill, 1874.

Probate files Isaac Tallmadge 158; Henry P.Strunk 137

Robinson, Nathaniel, Revolutionary War pension application

Schaghticoke cemetery records

Smith, Munson, probate file. In the archives, Rensselaer County Historical Society

Transcript of the Records of the Schaghticoke Dutch Reformed Church, 1903.

Troy “Daily Whig”, Oct 3, 1837, Oct 15, 1851, June 15, 1860, Feb 9, 1844, Sept. 1848

Troy “Daily Times”- article on Presbyterian Synod in 1865, mention of Noble in 1882, obit 1896, Aug 20, 1856, Sept 30, 1851, May 5, 1854

Union College, “A General Catalogue of the Officers, Graduates, and students of Union College,

1795-1868, pub. Munsell, Albany, 1868.

Williams College; General Catalogue of the Non-Graduates, 1920.

Williams College; General Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Williams College, 1910.